Book & Author

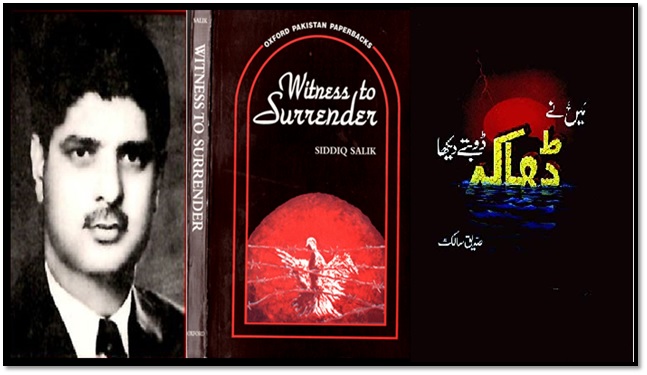

Siddiq Salik: Witness to Surrender

By Dr Ahmed S. Khan

Chicago, IL

When the final acts of drama “disintegration of United Pakistan” were played out in 1971, MajorSiddiq Salik was in Dacca; as a privileged observer and participant he saw the political and military actions which culminated in the Indo-Pakistan war and eventually led to the disintegration of Pakistan and creation of Bangladesh. After the fall of Dacca, he spent two years in Indian custody as a prisoner of war (POW). During the Indian custody he pondered over the facts and events, and analyzed the outcomes produced by the complex circumstances. He had produced a narrative embedded in facts with a comprehensive overview of the political turbulence of the time — a very first detailed professional account of the fall of Dacca in the form of Witness to Surrender (1977, Oxford University Press, Karachi). Later, in 1986, he published the Urdu version of the book as MaiN nay Dhakah Dub’tay Dai’kah (I saw the sinking of Dacca).

Brigadier Siddique Salik aka Siddiq Salik (September 6, 1935 – August 17, 1988) was born in a remote village of Manglia located in the Gujrat district of Pakistan. He studied English Literature and International Affairs at the Punjab University, Lahore. He began his career as a lecturer but soon turned to journalism, working in the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting before joining the Pakistan Army as a Public Relations Officer. He went to East Pakistan in January 1970 on a tour of duty which ended on 16 December 1971 with the fall of Dacca and creation of Bangladesh. He served as the public relations officer (PRO) in the Inter-Services Public Relations ( ISPR) East Pakistan of Eastern Command . After spending two years as a prisoner of war in India, he returned to the Army, which he served until his death in the fateful Bahawalpur plane crash in August 1988.

Saddiq Salik was a prolific writer, he authored nine books: Hamah YaraaN Dozakh (1974, Memoir), Witness to Surrender (1977), Ta Damay Tehreer (1981, Novel), MaiN Nay Dha’kah Dub’tay Dai’kha (1986), Pressure Cooker (1984), Wounded pride: the reminiscences of a Pakistani prisoner (1984), Emergency (1985), Salute: An autobiography (1986), and State and Politics: A Case Study of Pakistan (1987).

Witness to Surrender has three parts spanning over twenty-five chapters: Part I: Political (1. Facts and fears 2. Strain at the seams 3. Mujib rides the crest 4. The mockery of martial law 5. The free-for-all elections 6. The making of a crisis 7. Mujib takes over 8. Triangle) Part II: Politico-Military (9. Operation Searchlight-I 10. Operation Searchlight-II 11. An opportunity lost 12. Insurgency 13. Politics, at home and abroad 14. Closer to catastrophe) Part III: Military (15. Deployment for defeat 16. The reckoning begins 17. First fortress falls [9 division] 18. Collapse in the North [16 division] 19. Breakdown [14 division] 20. Chandpur under challenge [39 ad hoc division] 21. The Final retreat [36 ad hoc division] 22. Dacca: The last act, and 23. Surrender).

In the preface, the author sums up his arrival in and departure from Dacca, before and after its fall: “20 December 1971. Dacca had fallen but four days before. A transport plane of the Indian Air Force waited at Dacca airport to fly our top brass, including Lieutenant-General Amir Abdullah Khan Niazi and Major-General Rao Farman Ali, to Calcutta, as prisoners of war. They were also allowed their staff officers to share the air-lift and the subsequent ignominy. They all came and squeezed into the dark belly of the Caribou. The rickety machine jerked into life, groaned for some time, and finally took off. I was on board, too. Two years earlier, a PIA Boeing had landed me on the same tarmac. Life was very different then. The airport wore a gay look in the bright morning sun. The senior military officers were busy piloting the country to its democratic goal set by President Yahya Khan in his first address to the nation on 26 March 1969. Those in the saddle then, were in shackles now. A great change had come about. Personally, I had survived it, but the country had not. It was painful to recall the process; impossible to forget it. In this hour of agony, I decided to record my experience of the change. Recapitulating the process, I have mainly concentrated on events rather than personalities. I leave it to history to distinguish devils from dervishes. I am glad that neither General Headquarters nor the Government of Pakistan allowed me access to the official documents on the 1971 crisis. It has enabled me to retain my original impressions about the fall of Dacca. (The official documents quoted in the last part are only those which were available in Dacca even to the Indians after 16 December 1971). I shall welcome any official version which supplements, corrects; or contradicts my conclusions. 14 August 1976. Siddiq Salik.”

Reflecting on the demands of Mujibur Rehman, the author observes: “It was the first anniversary of the second martial law in Pakistan. Sheikh Mujibur Rehman was on his way to a rural town in East Pakistan to address an election rally. On the back seat of his rattling car sat with him a non-Bengali journalist who covered his election tours. He provoked Mujib on some current topic and quietly switched on his cassette tape recorder. Later, he entertained his friends with this exclusive possession. He also played it to me. Mujib's rhetorical voice was clearly intelligible. He was saying: `Somehow, Ayub Khan has pitched me to a height of popularity where nobody can say "no" to what I want. Even Yahya Khan cannot refuse my demands.' What were his demands? A clue was provided by another tape prepared by Yahya Khan's intelligence agencies. The subject was the Legal Framework Order (LFO) issued by the government on 30 March 1970. Practically, it was an outline constitution which denied a free hand to Mujib to implement his famous Six Points. He confided his views on LFO to his senior colleagues without realizing that these words were being taped for Yahya's consumption. On the recording, Mujib said: 'My aim is to establish Bangladesh. I shall tear LFO into pieces as soon as the elections are over. Who could challenge me once the elections are over?' When it was played to Yahya Khan, he said, 'I will fix him if he betrays me.'”

Recalling the sentiments of people in East Pakistan, the author states: “On the intellectual front, the situation was equally grim. Among my first contacts in Dacca, was the Bengali Resident Director of the Pakistan Council for National Integration. He took me round the library. Stopping before the arts section, he pulled out a well-produced book and said angrily, 'Look, this is what our Head Office (Rawalpindi) has sent us. What a waste of public money! Have you published any such artwork on a Bengali poet?' His fury was caused by Muraqqa-i-Chughtai, a rare work of art illustrating selected verses of the world-famous Urdu poet, Ghalib. He next stopped before the political section and said, 'Here, we have a whole shelf of books on your Quaid-i-Azam. I noted his accent on the word your and left.”

Recalling the postponement of the national assembly session, the author notes: “Lieutenant-General S. G. M. Peerzada, Principal Staff Officer to President Yahya Khan, made an ominous phone call to Governor Ahsan on 28 February to break the news that the President had decided to postpone the Assembly… As desired by Peerzada, Mujib was summoned to Government House at 7 p.m. the same evening and, after a long preparatory talk, Ahsan apprised him of the President's decision. Surprisingly, Mujib did not let fly. He retained his sweet reasonableness and said, 'I will not make an issue out of it provided I. am given a fresh date. It is very hard for me to handle the extremists within the party. If the new date is sometime next month (March), I will be able to control the situation. If it is in April, it will be rather difficult. But if it is an indefinite postponement, it will be impossible.' Before leaving the Government House, he said to Major-General Farman, 'I am between two fires. I will be killed either by the Army or extremist elements in my party. Why don't you arrest me? Just give me a ring and I will come over.' “

Discussing the Indian involvement, which climaxed in the open aggression of December, the author observes: “... Prominent Indian leaders and writers had declared their support for the rebels soon after the Army action. Mrs Indira Gandhi told the Lok Sabha as early as 27 March, 'I would like to assure the honorable members who asked whether timely decisions (about the East Pakistan crisis) would be taken, that it is the most important thing to do. There is no point in taking a decision when the time for it is over.’ Four days later, the Indian Parliament passed a Resolution saying, 'This house wishes to assure them [the rebels] that their struggle and sacrifices will receive the whole-hearted sympathy and support of the people of India.'2 The same day, Mr K. Subramanyum, Director of the Indian Institute of Strategic Studies, elucidated the Resolution at a symposium organized by the Indian Council of World Affairs in New Delhi. He said: 'What India must realize is the fact that the break-up of Pakistan is in our interest, an opportunity the likes of which will never come (again).' In the same speech, he called it the 'chance of the century' and expressed the Indian resolve to destroy Pakistan, its enemy number one.”

Reflecting on the high-powered Pakistani delegation, led by Bhutto, that was sent to China by General Yahya, the author notes: “The inclusion of Air Marshal Rahim Khan, PAF Chief and Lieutenant-General Gul Hasan, Chief of the General Staff…made it amply clear that China’s military help was also being sought…The delegation visited Peking in early November and held ranging talks with the Chinese leaders. During the visit, Bhutto was able to declare that 'the result of this meeting should be a deterrent to aggression'. This confirmed the earlier declaration by President Yahya Khan about Chinese help in the event of aggression against Pakistan. In addition, the press statements made then by Pakistani and Chinese leaders, encouraged one to believe that Chinese help would be forthcoming in the event of war.” [But like the American seventh fleet, the Chinese help never came, the Chinese turned out to be bystanders who watched from the sidelines the disintegration of Pakistan by Indians in collusion with the Soviets].

Referring to the potential American help, the author states: “…Washington was also asked whether the United States would honor her obligations under the bilateral treaty signed with Pakistan in the 1950s. But there too, we got the same advice instead of firm commitment of help. ‘Yahya showed me his correspondence with Nixon and the Chinese leaders, who were keenly hoping that political settlement with the Bengalis might be possible.'”

Commenting on the Indian diplomatic achievements, the author observes: “India achieved better diplomatic results than Pakistan. She followed up the Indo-Soviet Treaty with intense efforts to neutralize the threat of intervention by China or the USA. She invoked Articles 5 and 9 of the Treaty which make it obligatory for the signatories to consult each other 'in the event of either party being subjected to an attack or threat thereof'. Indian writers later confirmed that 'there is a military underpinning to the Agreement.’ Consequently, traffic between Moscow and New Delhi increased greatly. A five-member diplomatic mission headed by Soviet Deputy Foreign Minister Nikolai Firubin and a six-member military delegation led by the Chief of Air Staff, visited India in quick succession. The climax was a visit by Marshal Grechko, the Soviet Defense Minister, himself. There were also reports that an Indo Soviet liaison office had been established in New Delhi and Soviet experts and pilots were permanently associated with it. Indira Gandhi herself undertook a tour of important countries like the USA, West Germany and England from 24 October to secure their support or at least to neutralize any possible help for Pakistan from these quarters.”

Referring to the passive attitude of most countries and the twenty-sixth session of the General Assembly of the United Nations, the author notes: “The world watched with concern this drift towards armed confrontation between India and Pakistan but seemed unable or unwilling to act effectively to avoid the catastrophe…Pakistan readily agreed [to the UN resolution] but India refused. India, in fact, did not approve of any initiative which was likely to ease the situation in East Pakistan, She did not want to miss her 'chance of the century'.”

Commenting on the mood of General Niazi and defense of Dacca in the final act, the author observes: “I saw a slight change in General Niazi's mood during this hopeful spell of 10 to 13 December. He was still tense, but not completely broken. …By 10 December, the writing on the wall was so clear that Major-General Jamshed started exercising his duties as the defender of Dacca. General Niazi was thus relegated further to the background… Back in Eastern Command Headquarters, Brigadier Siddiqi talked of organizing street fighting in Dacca. But somebody pointed out, 'How can you organize street fighting in a city infested with a hostile population? You will be hounded, like stray dogs, by the Indians from one side and the Mukti Bahini from the other.' The idea was dropped. Looking at the enemy potential and our own resources, the Dacca defenses were like a house of cards. So far as street fighting is concerned, it was not a part of an overall operational strategy. It came only as a brainwave, signifying nothing. A drowning man futilely clutching at a straw.”

Recalling General Nagra’s bluff of encircling Dacca which General Niazi failed to comprehend, and which led to the fall of East Pakistan, the author states: “… Major-General Nagra of 101 Communication Zone, who was following the advance commando troops, held back on the far side of the bridge and wrote a chit for Lieutenant-General Amir Abdullah Khan Niazi. It said: 'Dear Abdullah, I am at Mirpur Bridge. Send your representative.' Major-General Jamshed, Major-General Farman and Rear-Admiral Shariff were with General Niazi when he received the note at about 9 a.m. Farman, who still stuck to the message for 'cease-fire negotiations', said 'Is he (Nagra) the negotiating team?' General Niazi did not comment. The obvious question was whether he was to be received or resisted. He was already on the threshold of Dacca. Major-General Farman asked General Niazi, 'Have you any reserves?' Niazi again said nothing. Rear-Admiral Shariff, translating it in Punjabi, said: Kuj palley hai? (Have you anything in the kitty?) Niazi looked to Jamshed, the defender of Dacca, who shook his head sideways to signify 'nothing'. 'If that is the case, then go and do what he (Nagra) asks,' Farman and Shariff said almost simultaneously. General Niazi sent Major-General Jamshed to receive Nagra. He asked our troops at Mirpur Bridge to respect the ceasefire and allow Nagra a peaceful passage. The Indian 'General entered Dacca with a handful of soldiers and a lot of pride. That was the virtual fall of Dacca. It fell quietly like a heart patient. Neither were its limbs chopped nor its body hacked. It just ceased to exist as an independent city…”

Recalling the surrender ceremony, the author states: “General Niazi drove to Dacca airport to receive Lieutenant-General Jagjit Singh Aurora, Commander of Indian Eastern Command. He arrived with his wife by helicopter. A sizable crowd of Bengalis rushed forward to garland their 'liberator' and his wife. Niazi gave him a military salute and shook hands. It was a touching sight. The surrender deed was signed by Lieutenant-General Aurora and Lieutenant-General Niazi in full view of nearly one million Bengalis and scores of foreign media men. Then they both stood up. General Niazi took out his revolver and handed it over to Aurora to mark the capitulation of Dacca. With that, he handed over East Pakistan!”

After arriving at Fort Williams, Calcutta, as POWs the author recalls his talk with General Niazi: “I took the opportunity of discussing the war, in retrospect, with General Niazi, before he had the time, or the need to reconstruct his war account for the enquiry commission in Pakistan. He talked frankly and bitterly. He showed no regrets or qualms of conscience. He refused to accept responsibility for the dismemberment of Pakistan and squarely blamed General' Yahya Khan for it. Here are a few extracts from our conversation: 'Did you ever tell Yahya Khan or Hamid that the resources given to you were not adequate to fulfill the allotted mission,' I asked. 'Are they civilians? Don’t they know whether three infantry divisions are enough to defend East Pakistan against internal as well as external dangers?' 'Whatever the case, your inability to defend Dacca will remain a red mark against you as a theater commander: Even if fortress defense was the only concept feasible under the circumstances, you did not develop Dacca as a fortress. It had no troops.' ‘Rawalpindi is to blame. They promised me eight infantry battalions in mid-November but sent me only five’…. ‘With what little you had in Dacca you could have prolonged the war for a few days more,’ I suggested. 'What for?' he replied. 'That would have resulted in further death and destruction. Dacca drains would have corpses piled up in the streets. Civic facilities would have collapsed. Plague and other diseases would have spread. Yet the end would have been the same. I will take 90,000 prisoners of war to West Pakistan rather than face 90,000 widows and half a million orphans there. The sacrifice was not worth it.' The end would have been the same. But the history of the Pakistan Army would have been different. It would have written an inspiring chapter in the annals of military operations.' General Niazi did not reply.”

Siddiq Salik had provided a vivid eyewitness account of the events leading to the fall of Dacca — it reveals a total leadership failure in all domains — political, military and foreign affairs. Witness to Surrender is a must read for all who want to learn from history.

(Dr Ahmed S. Khan - dr.a.s.khan@ieee.org - is Fulbright Specialist Scholar)