Book & Author

Natasha Bakht: Belonging and Banishment — Being Muslim in Canada

By Dr Ahmed S. Khan

Chicago, IL

“There is nothing that more closely resembles anti-Semitism than Islamophobia. Both have the same face: that of stupidity and hate.” - Nicolas Sarkozy, President of France

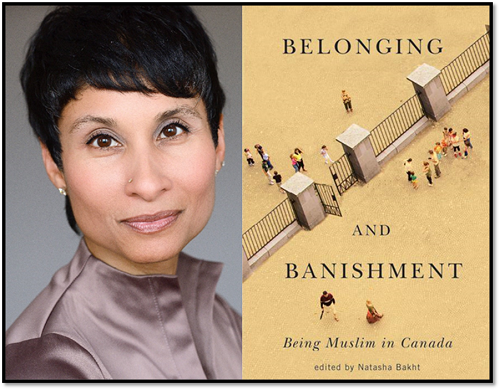

Belonging and Banishment , edited by Natasha Bakht, is a collection of essays — penned by a group of prominent Muslim professionals — exploring vital issues faced by Canadian Muslims, and the dubious role of the government of Canada — under pressure from the ‘war on terror’ lobby —and its various departments involved in entrapment of Muslims in the post 9/11 world. The editor, Natasha Bakht, is a professor of law at the University of Ottawa, and the Shirley Greenberg Chair for Women and the Legal Profession (2020-2022)

The book contains eleven narratives covering a wide range of topics: Introduction (Natasha Bakht), Muslims and the rule of law (Haroon Siddiqui), Bearing the name of the prophet [pbuh] (Syed Mohamed Mehdi), Knowing the universe in all its conditions (Arif Babul), Raising Muslim children in a diverse world (Rukhsana Khan), Islamic theology and moral agency: beyond the pre- and post-modern (Anver M Emon), Muslim girl magazine: representing ourselves (Ausma Zehanat Khan), Towards a dialogical discourse for Canadian Muslims (Amin Malak), Islamic authority: changing expectations among Canadian Muslims (Karim H Karim), and A case of mistaken identity: Inside and outside the Muslim ummah (Anar Ali), Victim or Aggressor: Typecasting Muslim Women for their Attire (Natasha Bakht), and Politics over Principles: The case of Omer Khadr (Sheema Khan).

Commenting on the delimitation of the book, the editor observes: “Contrary to most portrayals of Muslims in popular culture, we are not a monolithic group of people with a singular preoccupation. The intention of this book is to represent, in a thoughtful and nuanced manner, the diversity of Muslims in Canada, the issues that are of importance to them, and the problems that are thrust upon them. The book is by no means an exhaustive representation of Muslims and their views.”

Reflecting on the scope and objective of the book, the editor notes: “This collection on one hand conveys a picture of Muslims assaulted by the numerous discriminatory responses to terrorism prevalent in Canada, including outright human rights violations (Siddiqui, Bakht, S Khan). It also offers a portrait of Canada, with its protection of multiculturalism embedded in the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, as a haven from unjust and undemocratic regimes (Malak). It provides a complex idea of Muslims by illustrating disagreements within and between the many Muslim communities about a number of important issues (Emon, A Khan, Ali, Karim). And finally, it presents narratives steeped in history; the history of previous generations, of great Muslim philosophers, poets, architects, musicians, and scientists and the importance of passing this history and its lessons on to future generations (Mehdi, Babul, R Khan). Belonging and banishment take on very different connotations in each of these contexts…This collection attempts to create a space for Muslim voices less heard. Issues involving Muslim women are raised — the impact of their dress, their right to be free from violence, their claims of equality and religious freedom, and the appropriation of their stories by the media and others (Siddiqui, A Khan, Malak, Ali, Bakht)…Some commonalities that recur in these pages include the view that generally many Canadians do not know enough about Muslims or Islam and that what they do understand is driven by inaccurate mainstream descriptions (A Khan, Ali, Mehdi). The chapters in this book provide a counterpoint to misapprehensions about Islam and typical media depictions of Muslims. A number of the authors make comparisons to other communities, such as the Japanese Canadians, who have been targeted and subject to grave oppression during other perceived crises of security (Siddiqui, Malak, S Khan). These comparisons present important opportunities for alliance-building, a vital element in the struggle for justice.”

Expounding on the strengths of the contributions by a diverse group of professionals, the editor observes: “Haroon Siddiqui, editorial page editor emeritus and columnist for the Toronto Star, provides a comprehensive review of certain events of the past several years that indicate that Islamophobia has reared its ugly head in Canada. Siddiqui warns that deviations from the rule of law will not only affect Muslims in Canada but also erode the country's most fundamental democratic principles. Syed Mohamed Mehdi, professor of philosophy and a musician, has written a personal yet deeply political piece on bearing the name of the prophet [pbuh]. This chapter is rich in descriptive detail, with many hints of humor, and suggests that the portrait of a Muslim is not bound up in outward symbols but is one infused with the goals of social justice and other progressive ideals. Arif Babul, professor of physics and astronomy at the University of Victoria, provides a fascinating account of how one devout man reconciles his faith with his professional scientific pursuits. The reader is taken through a very compelling deconstruction of the archetypal conflicts between science and religion, to discover that the author, like other well-known scientists, comfortably occupies both of these realms. Rukhsana Khan, a writer of children's books, affords us a unique glimpse into her own childhood and the upbringing of her children…Anver Emon, professor of law at the University of Toronto, introduces the reader to the question of free will and determinism through premodern debates within Islamic theology…Ausma Khan is the Editor-in-Chief of the very successful and unique Muslim Girl magazine. Her chapter details the reasons behind the creation of this publication, including the reality that young Muslim girls are very much a part of the North American landscape…Amin Malak, professor of English at Grant MacEwan College, writes of a dialogical discourse for Canadian Muslims, he chronicles several significant areas of interest to Muslims and other Canadians attracted to the idea of sustaining a rich, equality-seeking and pluralistic society…Karim H Karim, the director of Carleton University's School of Journalism and Communication, presents very interesting research about the way some Muslims are reformulating the criteria required for competent Islamic authority in Canada…Anar Ali's demand for specificity in discussions about Muslims and Islam is a valuable lesson for those researching and writing about Muslim communities…My own piece tackles the seemingly ubiquitous issue of Muslim women's dress, but entirely within the Canadian context… Sheema Khan, columnist for the Globe and Mail, provides Canadians with a much-needed exposition of the tragic case of Omar Khadr, the minor who has been subjected to torture and detained in the demeaning conditions of Guantanamo Bay for the past six years. Khan delineates the numerous failures of successive Canadian governments to fight for the rights of Omar Khadr…The chapters in this book begin to answer the question of who a Muslim might be. The contributors to this collection in their diversity and with their impressive talents have begun to challenge what one ordinarily hears about Muslims. Their views are varied and perhaps even contradictory, but the richness of the critical exchange of ideas that they propose is a refreshing call for change.”

Haroon Siddiqui, in his narrative “Muslims and the Rule of Law,” observes: “Canada has not been immune from post-9/11 Islamophobia and the politics of fear. I say this not so much to echo the episodic Muslim discourse of victimology but as a Canadian saddened by the impact of anti-Muslim prejudice on the Canadian polity, whose defining premise is the equality of all people living under one law, uniformly applied. In support of this proposition, the following episodes jump to mind: • The Maher Arar tragedy. • The alleged Canadian complicity in the reported torture in Syria of three other Canadian Arabs. • The sad saga of five Arabs caught in the dragnet of the federal security certificates. • The 2003 mistaken arrest of 23 Muslim men of Pakistani and Indian origin in Toronto as ‘suspected terrorists,’ but against whom not a single terrorism-related charge was laid. • The 2006 arrest of 18 Toronto-area Muslims on terrorism, related charges, a case so poorly formulated that charges had to be dropped against as many as seven of the accused even before the trial began…”

Siddiqui, reflecting on ‘Drawing Lessons’ notes: “As we have seen, many of the controversies involving Canadian Muslims are draped in double standards, hypocrisy, or confusion. Most of the tensions surrounding Muslim religious practices are not exclusive to Muslims. People of other faiths face similar challenges in balancing their constitutional right to freedom of religion with other rights…It is also wrong to assume that Muslims are not adapting to Canadian values. They are — because they must, in that all must obey the rule of law, and there's no suggestion that they aren't, compared to the rest of the population. Polls also show that Muslims in Canada, the United States and across Europe share the same sense of belonging and hold the same values, hopes, and fears as their fellow-citizens (Adams, Esposito, Pew Global Attitudes Project). Canadian Muslims are also not making unreasonable demands, as the Bouchard-Taylor commission concluded. Addressed to Quebecers, the commission's findings are relevant to all Canadians. ‘The right to freedom of religion includes the right to show it,' said Taylor and Bouchard. They argued that the display of religion in public spaces advances the common good, by compelling all citizens to ‘get to know those of the Other, (rather) than deny or marginalize them.’”

Referring to the mistake of painting all Muslims with the same brush, Siddiqui states: “A common mistake made by non-Muslims is to conflate Canadian Muslims with Muslims the world over. This is a by-product of a post-9/11 malaise: Laying collective guilt on all Muslims for the actions of a few. Law-abiding Muslims are no more responsible for 9/11 and the London subway bombings and other acts of terrorism than Japanese Canadians or Japanese Americans were for Pearl Harbor, or German Americans, German Canadians and German British were for Nazism. It is useful to recall what Anne Frank, hiding from the Nazis in Amsterdam during World War II, wrote in her famous diary, on May 22, 1944: "When a Christian does something wrong, it's his fault. When a Jew does, it's the fault of all Jews" (Frank, 299). Yet it is often demanded of Canadian Muslims that they pronounce themselves on this or that Muslim atrocity somewhere in the world. Canadian Muslims live here in Canada, not there.”

Syed Mohamed Mehdi, in his essay “Bearing the Name of the Prophet [pbuh]” — The Many Meanings of Mohamed (One Who is Praised), observes: “In April 2004, I was flying to Chicago for a job interview at the American Philosophical Association's Midwestern meeting. Flying from Montreal, I had to clear US customs before boarding my plane. After showing my passport to an agent in line, I was sent into a separate room to be dealt with by a special officer. My passport was handed over to him in a see-through plastic bag. After making a few phone calls, he gestured for me to enter his office. I was a bit nervous. I wanted to get on my flight. He broke the ice with, ‘You have a very interesting name.’ When I politely thanked him for the compliment, he revised his statement: ‘You share your name with some very interesting people.’”

Mehdi, expounding further on living with his name, states: “My identification with progressive ideals has, perhaps ironically, led me to see that I should not fear the Muslim identity suggested by my name. During this same time, I have seen many who, as a result of their identification with Islam, have come to embrace a progressive political outlook, emphasizing the basis in Islamic beliefs for justice, equality, freedom, and pluralism. This convergence, although it hasn't been widely spoken of, is one of the few positive consequences for Muslims of the ‘war on terror’ and its broader context. There is a potential for building on this in Canada, for slowly developing a broader sense of what it means to be a Muslim, grounded in those elements in Islam that have historically taught us about what it means to live well together respectfully, lovingly, as brothers and sisters. But this will only be possible as we begin fearlessly to explore the complexity of Muslim culture and the many meanings of ‘Mohamed.’”

Arif Babul, in his essay “Knowing the Universe in All its Conditions,” observes: “I am an astrophysicist, a physical cosmologist, and my work involves trying to understand how matter in the Universe, having emerged from the fires of the Big Bang in an exceedingly smooth and homogenous state nearly 14 billion years ago, managed to organize itself into something that resembles a network of matter filaments, bejeweled necklace strands if you will, strung with millions of galaxies and occasionally punctuated by massive swarms of up to a thousand bright galaxies held together by their mutual gravity, and all woven together in a glittering cosmic web draped across the incomprehensibly vast regions of space. And I am Muslim…In fact, my father took great pains to teach me that this was part and parcel of the 1400-year-old intellectual heritage that the Ismailis are heir to. The resulting discourse sometimes led to my being introduced to the ideas expounded by Muslim scientists, philosophers, and poets such as Ibn al-Haytham, Nasir Khusraw, al-Tusi, Ibn Sina, Ibn Arabi, Rumi, Iqbal, etc.”

Anver Emon cites Ibn Taymiyya in an essay titled Islamic Theology and Moral Agency: Beyond the Pre- and Post-Modern: “The distinction [between the two levels of qadar analysis] leads to [understanding] the difference between benefit and harm, and their causes. This difference is understood by recourse to sensory perception, reason, and scripture, and is agreed upon both by old and recent scholars. It is known by animals and exists in all created things. When we establish the difference between good (al-muhsanat) and evil (al-sayyi'at) — which is the difference between the good (hasan) and the bad (qabih) — the difference relates to this [second level of investigation] … Although Muslims disagree on the theology of free will or determinism, the purpose of this article has been to illustrate that more is at stake than just debating the omnipotence and the glory of God. Certainly, the Islamic conception of God emphasizes His power and authority over all things in creation.”

Amin Malak, in his narrative “Towards a Dialogical Discourse for Canadian Muslims,” observes: “Let me begin with a heart-warming incident that should inspire any caring Canadian. In the turbulent days immediately following the 9/11 horror, the leaders of the Jewish and Christian communities of Edmonton realized that the Muslims of Alberta's capital were in for a rough time. In an impressive gesture of solidarity, the leaders of the two Abrahamic faiths, accompanied by senator Doug Roche and religious studies professor Earle Waugh, went to Al-Rasheed Mosque, the largest in the city, and publicly attended the Friday prayer. Some joined the worshippers in the prayer hall — normally accessible only to Muslims. A minister from the United Church of Canada, Bruce Miller, even prayed with the Muslim worshippers, emulating their ritualistic gestures: bowing, kneeling, standing, and mouthing the Muslim article of faith. Only a confident, caring culture can perform such an elegant proactive gesture. Only a genuinely generous community appreciates the generosity of other communities extending such a warm hand. That Islam and Muslims are now part of Canada's constituent mosaic is an indisputable reality. Given the diversity of perspectives and voices emanating from Muslims living in the country, a language of understanding and respect must emerge, evolve, and flourish to embrace the precious reality of the Muslim strand interwoven into the Canadian fabric. Many well-intentioned Canadians, Muslims and non-Muslims, worked hard to turn this transformative presence into a meaningful reality, irrespective of occasional clouds of misunderstanding and tension. Despite its acknowledged imperfections, Canada remains the best space and environment for Muslim culture and identity to flourish in a pluralist, secular state. This means that the Muslim communities should be able to participate in Canadian life in a way that does not violate the ethos of the cultural mosaic that characterizes Canada and does not violate the pivotal values of Islam.”

Malak, further observes: “While some Muslims were living in Canada in the years preceding its official founding in 1867, they began arriving in large numbers only in the last five decades, thanks principally to Pierre Trudeau's visionary multicultural policies. As such, Canadian Muslims cannot afford to isolate themselves from their fellow citizens. Being here for all immigrants means engagement with new realities, transacting with different people, and facing paradigms of conduct quite different from their cultures of origin. For a meaningful immersion in the new reality, newcomers and their recipient communities have to undergo processes of adjustment, which might involve moments of tension and misunderstanding. However, over time and after the enlargement of the circles of interaction, a modus vivendi emerges, whereby patterns of mutual cooperation develop.”

Karim H Karim, in his essay “Islamic Authority: Changing Expectations Among Canadian Muslims,” citing a doctoral student of Muslim architecture in Montreal, states: “I think we as Muslims, we have the most widely open epistemology. Our epistemology encompasses different spectrums of human knowledge: what's wrong, what's right, how we can know things, and the veracity of things, how we establish the veracity of the things which we know . . . it's not only from [a] Muslim point of view but also through the critique of Muslim scholars who critique modernity, that modernity is a reductivist paradigm. So, we have to realize that when we are living in Western society, that this culture doesn't account for many things which we hold to be necessary and actually [are] at the basis of our epistemology. This will create some kind of miscommunication, or like inability on our part to explain things, because our project is larger. They have fewer colors in their spectrum…”

Karim concludes his essay, by observing: “Muslim individuals are looking at their roles as citizens of Western countries together with the concepts of being good Muslims. Such thought has significant implications in contemporary times when the followers of Islam are facing a range of social options that include assimilation into secularism, at one end, and embracing religious extremism, at another. A number of interlocutors mentioned the importance that they gave to living balanced lives. The solutions that Muslims in the West will choose will differ between communities and individuals; however, the discursive journeys towards these ends and their outcomes will necessarily have implications for society at large.”

Sheema Khan, in her essay “Politics Over Principles: The Case of Omar Khadr,” notes: “Muslims need to stand up for justice in a balanced way that protects human rights and security. It is civil society that has shown true strength of character during these troubled times. NGOs, human rights groups, journalists, and the courts have slowly, but surely, fought for justice for those wrongly treated. We cannot take the freedoms and rights that we have for granted. For these have been established through hard work and sacrifice by many Canadians who preceded us. In one aspect, Canada is a compassionate meritocracy woven by the efforts of countless women and men. We must join together to uphold values that we cherish, such as freedom, genuine respect, and fairness. In looking back, we see that dark episodes of ethnic profiling were punctuated by the enlightened efforts of those who fought back, leading to the evolution of social justice and law for the benefit of future generations. In the process, each group became further entrenched within the Canadian mosaic. At this point in Canadian history, Canadian Muslims and Arabs face the pernicious specter of ethno-religious profiling and a devaluation of their citizenship. If we are to learn anything from history, it is that abuses of government power cannot be left unchallenged. Canadians of good conscience must join together to fight for the basic human dignity of their fellow citizens. With each fresh revelation about human rights abuses perpetrated by the Canadian government in the name of security, we must heighten our vigilance against abuses of power, and demand due process for those who are detained or exiled without charge. Let's take on this responsibility with confidence, tenacity and courage, remembering the Qur'anic verse: God does not place a burden on anyone heavier than one can bear.”

Belonging and Banishment — Being Muslim in Canada , edited by Natasha Bakht, presents a collection of eleven narratives and insights — penned by a diverse group of Canadian Muslim professionals — exploring matters of Muslim faith, identity, diversity, and human rights. It is an important book that chronicles post-9/11 challenges, trials and tribulations of Muslims in Canada.

(Dr Ahmed S. Khan - dr.a.s.akhan@ieee.org - is a Fulbright Specialist Scholar, 2017-2022)