Book & Author

Friedman, Stiglitz and Wildavsky: Globalization

By Dr Ahmed S. Khan

Chicago, IL

“Where globalization means, as it so often does, that the rich and powerful now have new means to further enrich and empower themselves at the cost of the poorer and weaker, we have a responsibility to protest in the name of universal freedom.”

—Nelson Mandela

“Globalization is a complex issue, partly because economic globalization is only one part of it. Globalization is greater global closeness, and that is cultural, social, political, as well as economic.”

— Amartya Sen

Today, the world has been globalized, but globalization has become a controversial phenomenon. On one side of the globalization debate are the proponents, who believe that it is the panacea for all global economic problems, and on the other side the opponents, who claim that it is promoting economic inequity.

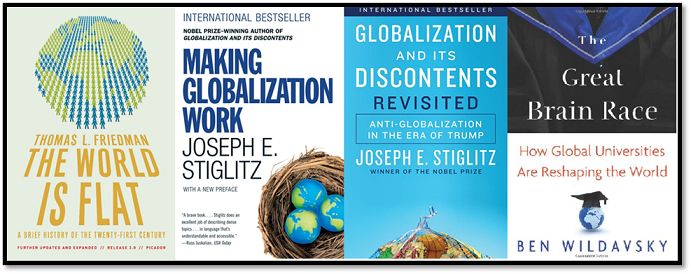

Is globalization really working? On the pro side of the globalization debate is Thomas Friedman, the Pulitzer Prize-winning columnist of the New York Times. In his book The World is Flat: A Brief History of the Twenty-First Century, he argues that technological innovations and advances have led to a new form of globalization which is flattening the global playing field. Friedman argues that globalization has empowered millions of tech-savvy people all over the world and enabled them to learn the new rules of the global economic system. He has defined three eras of globalization: Globalization 1.0 (1992-1800 AD), Globalization 2.0 (1800-2000 AD) and Globalization 3.0 (2000 – Current era).

Friedman observes that the convergence of technologies has flattened the world with new business processes and enabled 3 billion people to participate in defining the course of the 21 st century. The “key flatteners” are information technologies — the invention of graphical user interface (GUI) for the personal computer (in 1980s), development of the Internet infrastructure and protocols (SMTP: e-mail, HTML: webpages, and TCP/IP: interconnection of network devices, in 1990s) — that opened up new modes of collaboration and cooperation from widely dispersed people around the globe.

How to fix problems associated with Globalization? Friedman argues that Globalization is like a large computer program that has lots of bugs and does not follow an open systems architecture. To fix the problems patches are issued continuously, likewise due to lack of equitable standards to resolve crises arisen by globalization lots of patchwork must be used continuously to fix crises arisen because of globalization.

On the opposite side is Joseph Stiglitz, the winner of the 2001 Nobel Prize in economics. In his books Globalization and its Discontents, and Making Globalization Work, he paints a less rosy picture and argues that globalization produces winners and losers; further, under the current rules of international trade, there are more losers than winners. He argues that a “one size fits all” solution does not work for everyone. He observes, “The hope of globalization was that it was like a rising tide lifts all boats, and so the poorest would see themselves go up. But the way it was managed, it might be more likened to riptide knocks over the weakest boat, and without life vests, without safety nets, a lot of the people in those weaker boats drowned.”

Stiglitz has analyzed how multilateral institutions like the World Bank and international monetary fund affected policy and the lives of the ordinary folks and offers recommendations for fixing the current international economic system in order to create a fairer world — to make process work for the poor and for developing countries.

Referring to the systemic problem and how Globalization has increased the gap between the rich and the poor in many countries, Stiglitz observes: “But the debt contracts that are signed around the world, typically by poor countries, involve short-term contracts dominated in hard currency. The result is that the poor countries bear an enormous amount of risk associated with interest rate and exchange volatility, and that has meant there have been large number of crises.”

Why has globalization not worked? Stiglitz observes: “Economic globalization has outpaced political globalization. Economic globalization has meant we are more interdependent, more integrated, as a global economy; and more integrated, more interdependence, means there is more need for cooperative action. We have to do something together — set standards, set rules of the game. But we don’t have the political institutions by which to do that democratically, nor the mindset to do it in ways that are fair. Too often, notions of fairness stop at the border.”

Subscribing to Friedman’s views, former US News & World Report education editor Ben Wildavsky in his book The Great Brain Race: How Global Universities are Reshaping the World expounds the thesis that the growing demand for intellectual power is transforming higher education and that globalization in education is creating “free trade in minds.” A global competition to attract top students and faculty is creating new opportunities for developing and acquiring intellectual capital to compete in the knowledge economy.

The book has six chapters depicting stories and facts about the impact of globalization on higher education. In Chapter 1, the author discusses the rapid growth of student mobility and the intense competition among universities eager to expand their market share by recruiting smart students. He also discusses growing faculty mobility, where universities hire more foreign professors. The author argues that mobility can apply not just to physical movement but also to movement of ideas. Globally around three million students are enrolled in educational institutions located outside of their native countries. The United States has the largest share of international students — 22 percent - and 64 percent of all foreign engineering graduates.

The author also notes that in the United States scholarly mobility has been slowed or halted by visa policies that are typically not protectionist in any explicit sense but nonetheless have unfortunate effects. Stepped up security review in the years since September 11 has led to a decline in student visas issued for Pakistan and Middle Eastern countries.

In the domains of academia, Pakistan has not been a beneficiary of globalization dividends, and is a prime example of Stiglitz’s thesis. According to the Institute of International Education, since 2001/02, the number of Pakistani students in the US has dropped, pushing Pakistan out of the top 20 sending places of origin in 2006/07. The number of students from Pakistan continued to decline, by 1% in 2007/08, 0.9% in 2008/09 and 1.4% in 2009/10. For the 2020/21 academic year 7,475 students from Pakistan were studying in the United States, a -5.8% change from the previous year.

India, on the other, emerged as a major beneficiary of globalization, a perfect example of Friedman’s model. According to the Institute of International Education (IIE) data, for the 2009/10 academic year, 104,897 students from India were studying in the United States (up 1.6% from the previous year). India is the second leading place of origin for international students in the US after China…for the 2009/10 academic year, 104,897 students from India were studying in the United States (up 1.6% from the previous year). India is the second leading place of origin for international students in the US after China…2000/01 marked a new surge in enrollments from India, with an increase of 30%, followed by two more years of double-digit growth (22% in 2002/03 and 12% in 2003/04). After a small increase in 2004/05 and a decrease in 2005/06, the number of students from India increased by much larger percentages in 2006/07, 2007/08 and 2008/09. Students from India make up slightly more than 15% of the total foreign student population in the United States.” For the 1994-2010 academic years, more than one million visas were issued to students from India. For the 2020/21 academic year, students from China (317, 299) and India (167, 582) accounted for 53% of all international students in the United States. For the 2018/19 academic year, the Chinese students paid around $15 billion in tuition at US schools.

In Chapter 2, the author explores the phenomenon of branch campuses established in the Middle East and Asia by Western universities. These campuses have faced the challenges of expense controversy and closure due to low student enrollments. In Chapter 3, the author probes the ways in which nations are expanding and improving their own universities. He mentions the examples of China and India, where governments are spending vast sums to improve their education standards.

In Chapter 4, the author expounds on the new world of college rankings. An inquiry which is too vague, and not very relevant to the theme of the book. In Chapter 5, the author discusses the plans of private American universities, institutions to expand globally, and the need for tighter regulations for promoting academic integrity. The author observes that globally, for-profits represent a huge proportion of student enrollment — 80 percent in South Korea, 77 percent in Japan, and 75 percent in India and Brazil. But despite their success in terms of enrollment and reaching and capturing new markets, they face huge skepticism from analysts and government regulators in terms of quality of education and academic integrity issues for their online programs.

In Chapter 6, Wildavsky amplifies and expands his core argument that higher education has become a form of international trade and that the beneficial principle of free trade should be applied to scholarly exchange just as to the other parts of the global economy.

The author argues that academic protectionism, immigration barriers, and fretting about the growing prowess of overseas universities have no place in a worldwide knowledge economy and that Ideas are the main currency of the new economy. The book lacks a scholarly tone but provides a plethora of facts and stories.

Wildavsky concludes the book with the prediction that economic returns of higher education are so significant that nations will continue to have powerful incentives to expand their university systems and to attract talented students and faculty from near and far. In a nutshell, the author’s main thesis is, “The globalization of higher education should be embraced, not feared.” But it appears that policy makers in the developing world — in contrast to Friedman’s views — are now following Stiglitz's advice to protect their public universities from the riptide of globalization.

(Dr Ahmed S. Khan ( dr.a.s.khan@ieee.org ) is a Fulbright Specialist Scholar - 2017-2022).