Book & Author

Zulfikar Ali Bhutto: The Myth of Independence

By Dr Ahmed S. Khan

Chicago, IL

“We cannot escape the responsibilities of leadership. It is for the leaders to hold high the banner of independence and march forward with confidence in a spirit of dedication. Our choice is whether to face the struggle or succumb to external pressures and become a tombstone of the cold war.”

- Zulfikar Ali Bhutto

After WWII, many African and Asian countries gained independence from colonial powers. But their dreams and aspirations for freedom, economic growth and prosperity have yet to materialize. People of these nations wonder if the colonial era has really ended or merely replaced by an economic system dictated by international financial institutions and multinational corporations. Since the 1950s Pakistan has also struggled to develop a foreign policy based on its interests, uninfluenced by the global requirements of the Great Powers.

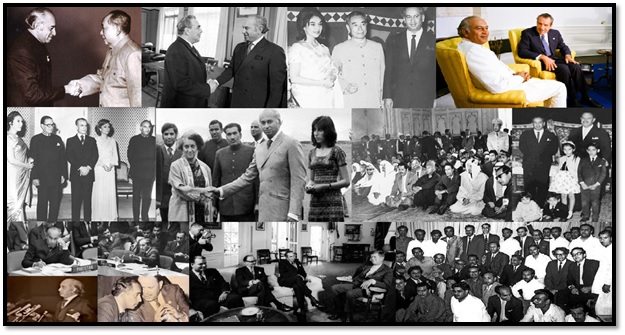

In The Myth of Independence Zulfikar Ali Bhutto (ZAB) aka Quaid-e-Awam (leader of the people) explores the challenges of establishing a foreign policy that safeguards the independence and sovereignty of Pakistan viz a viz interplay of global and regional powers. Zulfikar Ali Bhutto (January 5, 1928 – April 4, 1979) had served as the chief martial law administrator (1971-1973), president (1971-1973), prime minister (1973-1977) and foreign minister (1963-1966) of Pakistan. He was also the founder and chairman of Pakistan People’s Party (PPP). The book was published after the 1965 India-Pakistan war; its pdf versions are available on the Internet.

ZAB recommends that Pakistan must develop and support good relations with all global powers —United States, Russia, and China — and all neighbors and regional powers on the basis of mutual goodwill and self-respect. ZAB’s narrative, for an independent and sovereign foreign policy, is spread over twenty chapters: 1. The Struggle for Equality, 2. Global Powers and Small Nations, 3. American Attitudes towards Partition and Indian Neutralism, 4. India seeks American Support against China, 5. America aids India and ignores Pakistan, 6. American Policy to bring Pakistan under Indian Hegemony, 7. Collaboration with India on American Terms, 8. American Demands and the Choices before Pakistan, 9. The Indo-Pakistan War and its Analogies, 10. Relations with Neighboring Countries and Some Others, 11. Pakistan and the Vietnam War, 12. Sino-Pakistan Relations, 13. Relations with European Powers and Great Powers, 14. Some Conclusions, 15. The State's Best Defense, 16. Deterrent against Aggression, 17. How to Face the Looming Crisis, 18. The Origins of Dispute with India, 19. Confrontation with India, and 20. Epilogue.

In the preface ZAB explains how he got involved in international relations: “The study of history, an acquaintance with the problems of underdeveloped countries, and my own penchant for international politics justified, I imagined, my ambition to serve Pakistan as its Foreign Minister. That ambition was fulfilled when I was made Foreign Minister in January 1963, on the death of Mr Mohammad Ali Bogra. Before that date, however, I had had to deal with international problems of fundamental importance to the interests of Pakistan. In December 1960, in my capacity as Minister for Fuel, Power and Natural Resources, I went to Moscow to conduct negotiations with the Soviet Union for an oil agreement. I mention this fact because it marked the point at which our relations with the Soviet Union, most unsatisfactory until then, began to improve On my return from the famous General Assembly Session of 1960 which was attended by Premier Khrushchev, Presidents Nasser and Soekarno, Mr Macmillan, Pandit Nehru, Senor Fidel Castro, and many other eminent statesmen, I was convinced that the time had arrived for the Government of Pakistan to review and revise its foreign policy. I accordingly offered suggestions to my Government all of which were finally accepted. This was before I became Foreign Minister. The ground was thus prepared for my work, by changes introduced at my own insistence, when I took charge officially of the conduct of foreign policy as Foreign Minister.”

ZAB, reflecting on the mistakes made in devising and conducting the foreign policy, states:“ The reader will discover for himself in the pages of this book what opinions I hold, what my attitude is to world problems, what mistakes I believe were committed by Pakistan in dealing with foreign powers—particularly with Global Powers—and how those mistakes may be remedied, what my proposals are for a foreign policy adequate to avert the dangers which now threaten the country. It would be pointless to attempt to summarize these views within the brief compass of a Preface. Nevertheless, it is worth emphasizing that the policy of close relations with China, which I formulated and put into operation, is indispensable to Pakistan, that in dealing with Great Powers one must resist their pressures by all possible means available, when they offend against the Nations welfare, and that compromises leading to the settlement of disputes by default or in an inequitable manner strike at the roots of national security, even existence. If I assume responsibility for certain policies, I also admit that I made every effort to carry them into effect until I left office in June 1966. Though tempted to write at greater length about the Indo-Pakistan war of 1965 and the subsequent Tashkent Declaration, I decided, for various reasons, to defer discussion of these and other topics to a later date. The truth of this chapter of history has yet to be told. I confess that this book has been written in haste, in circumstances over which I had no control, in a race against time which is dragging Pakistan, with giant strides, to the crossroads whence all ways but one lead to destruction. Z.A.B. Karachi, November 1967.”

Discussing the post WWII rules of conducting foreign policy by smaller nations, ZAB notes: “The emergence of these [Global] Powers in the last twenty years has changed the whole concept of conducting affairs of state. The task of smaller nations, in which category all the developing nations fall, in determining their relationship with Global Powers and in furthering their national interests has become more complex and difficult. The small nation which does not understand the new rules of diplomacy is doomed to frustration, a sense of helplessness, isolation and, perhaps, eventual extinction. As a developing nation, Pakistan must understand how to conduct its affairs in this new situation.”

ZAB further observes: “…the emergence of three Global Powers and the struggle for the domination of men’s minds all over the world—requires great vigilance on the part of statesmen of the smaller nations who control the destinies of their people. Their method of approach to the Global Powers in the conduct of their foreign policy and their solidarity among themselves will ultimately determine whether the nations they guide will retain their independence and self-respect in the world of tomorrow.”

Highlighting the importance of leadership, ZAB states: “We cannot escape the responsibilities of leadership. It is for the leaders to hold high the banner of independence and march forward with confidence in a spirit of dedication. Our choice is whether to face the struggle or succumb to external pressures and become a tombstone of the cold war. It is written in the Holy Koran: ‘And we shall give the joys of victory to those who are oppressed, and who struggle to uphold justice and freedom on the face of the earth; it is they whom we shall raise to be leaders, and it is they who shall be the heirs who shall build up and develop the equal well-being of Man.’”

Presenting the evolution of Pakistan-United States relationship, ZAB observes: “On 19 May 1954, after some hard negotiations, Pakistan and the United States of America concluded the Mutual Defense Assistance Agreement and entered upon a period of association euphemistically called a ‘special relationship’. For over twelve years, the United States provided Pakistan with considerable economic and military assistance. In 1959, misunderstandings arose in the relations between the two countries and have since grown and multiplied, especially after the Sino-Indian conflict. Relations have followed a checkered course, sometimes bearing on economic matters and sometimes, more profoundly, on political issues. The pendulum has swung from one extreme to the other, from association to estrangement. There was a time when Pakistan was described as the most ‘allied ally’ of the United States and, to the chagrin of other ‘client States’ of Asia, it was asserted by President Ayub Khan, in an address to the United States’ Congress in 1961, that Pakistan was the only country in the continent where the United States Armed Forces could land at any moment for the defense of the ‘free world’. When, during the U-2 episode, in an attempt at refined diplomacy, the United States prevaricated with ambiguous statements, Pakistan, more royalist than the monarch, openly admitted that the aircraft had taken off from Pakistan and that, as a staunch ally of the United States, Pakistan was within its rights to allow it to do so. In less than a quarter of a century, Pakistan’s relations with the United States and India have completed a cycle in each case. Vigorous efforts have been made to drag Pakistan away from the posture of confrontation to cooperation with India and, in this very process, relations with the United States have changed dramatically from those of the most ‘allied ally’ to the point at which it is alleged that there is ‘collusion’ between Pakistan and the United States’ principal antagonist—the People’s Republic of China.”

Referring to Pakistan-China relations, ZAB notes: “On 1 March 1964, Mr George Ball, the United States’ Undersecretary of State, warned Pakistan that ‘we very much hope President Ayub will not carry relations with Red China to a point where it impairs a relationship which we have and an alliance which we have’. He added that ‘what it [Pakistan’s relations with China] reflects in terms of an attitude is something about which we are very much concerned. We watch this very carefully.’ And he went on to say: Pakistan ... is very clear about her enemy being the Soviet Union and about the fact that she is a member of an alliance which is directed against Communist aggression, and I am sure that if there were any move by Red China against Pakistan, then Pakistan would respond with military defense. Her discussions with Red China up to this point have not suggested otherwise, but we are watching this relationship with great attention.”

The author has explored in depth the United States’ tilt toward India during the 1960s which adversely changed the balance of power for Pakistan — a member of CENTO and SEATO. ZAB observes: “The writing on the wall became clear beyond doubt in 1964, when the United States decided to give long-term military assistance to India despite earlier decisions, made in deference to Pakistani fears, to provide India with ad hoc assistance subject to review. In taking this new decision the United States took the risk of further straining relations with its most committed Asian ally. When Pakistan swallowed this unpalatable decision and chose not to shirk her cold war commitments in the interests of her own security, the United States concluded that she would not take any counter-measures and accordingly accelerated the rate of aid to India. Pakistan has lost many excellent opportunities to redress her position, and the time for action is slipping past. Timing and initiative, essential ingredients of successful political action, have been as little evidenced in her policies as sound political judgment.”

Reflecting on United States’ continued support to India, ZAB notes: “After the assassination of President Kennedy in November 1963, his successor, President Johnson, continued on the same path. On 27 December of that year Time magazine reported that Nehru had now agreed to accept the Western air defense umbrella and the United States’ Seventh Fleet in the Indian Ocean, but, in return, he had asked for $1 billion military assistance to secure his concurrence. In March 1964 the United States’ defense Secretary, Mr Robert McNamara, repeated the American determination to continue the program of military support to India.”

ZAB further notes: “Pakistan wants to have friendly and normal relations with the United States, a Global Power that has contributed considerably to Pakistan’s development. When displeasure with India brought the United States closer to Pakistan, we came to the hasty conclusion that it was our permanent, natural friend; but in international politics the phrase ‘natural friend’ has no meaning. Its use betrays a romantic outlook on world affairs. Common interest between states exists, but no permanent, natural friendship. Our relations with the United States have suffered partly because we refused to enlarge the Vietnam war by bearing arms on their side. A time may come when the United States wishes to leave the battlefield in search of peace and Pakistan might then have a notable contribution to make.”

Expounding on Pakistan’s relations with neighboring countries, ZAB writes: “Pakistan has established a model relationship with Iran and Turkey, and this fraternal association is an increasingly powerful factor in Asia. The Regional Cooperation for Development, popularly called RCD, will bring our countries closer together as it is based on equality, mutual assistance, and friendship.”

Reflecting on the relations between the United States, Soviet Union and China, ZAB notes: “Diplomacy is a flexible art. What appears to be impossible today is possible tomorrow. If President Kennedy had not been assassinated, the Vietnam war might well have taken a different course. A constructive dialogue might have begun between China and the United States, on the lines of that begun between President Kennedy and Premier Khrushchev in Vienna, which led to the detente between the United States and the Soviet Union.”

Discussing Pakistan’s relations with three European powers — France, Germany and Britain — ZAB observes: “It remains to be seen which of the three quasi-Great Powers of Western Europe is capable of making the greatest contribution to Pakistan’s national cause in the foreseeable future; but on the basis of her present policy, France seems the most likely. Her support for the principle of self-determination, her effort to free herself from the Atlantic hegemony, and her comprehension of Asian problems has resulted in France’s good relations with Pakistan…”

On formulating an independent foreign policy, ZAB states: “We must maintain a non-committal attitude in global confrontations, but, at the same time, take a clear and independent position on world issues affecting the rights of peoples and nations to equality, self-determination, and economic emancipation. Uninfluenced by the attitude of other nations, Pakistan must always oppose aggression and stand behind the victims, in conformity with the noblest norms of its ideology. We should demonstrate strict neutrality in the ideological confrontation of the Global Powers. In determining her relations with such Powers, Pakistan must also take into account her geographical situation and the support she receives in her own just causes. She must formulate her policies on the merits of each case, without taking a predetermined position in the global rivalries. These policies must be in accordance with the concept of non-interference in the internal affairs of a country and self-determination for all nations. She must refrain from accepting preconditions which limit her freedom of action in any respect in the discharge of her national and ideological obligations.”

ZAB further observes: “In view of past experience and other considerations Pakistan must pursue three principal objectives: 1. A policy of friendship and good faith with China, a Great Power with whom its basic interests conform. 2. Good relations with the United States and the Soviet Union, but without preconditions and on the basis of non-interference; also, with the nations of Eastern and Western Europe, especially France, Germany, Britain, Romania, Czechoslovakia, and Poland. 3. The strengthening of the Third World—the under-developed nations of Latin America, Asia, and Africa, and, in particular, Muslim nations and neighboring countries.”

Advising on how to face the looming crisis, ZAB states: “A national crisis is a call to national greatness, and must be met with a spirit of dedication. Muslims cannot be better inspired to face such a challenge than by heeding the words of the Holy Koran: ‘Fighting in defense of Truth and Right is not to be undertaken light-heartedly, not to be evaded as a duty. Life and Death are in the hands of God. Not all can be chosen to fight for God. It requires constancy, firmness and faith. Given these, large armies can be routed by those who battle for God.’”

Predicting the potential of relations between the United States, Russia and China viz a viz India, ZAB observes: “The present situation cannot last indefinitely. The attitudes of Global Powers, as we have seen, are capable of changing. In international dealings there is no such thing as an ‘irrevocable constant.’ That is why India is afraid when she hears talk about bridges of understanding between China and the United States. With the passage of time, when a modus vivendi is struck between the United States and China, or between China and the Soviet Union, India will find herself in isolation.”

Reflecting on the Pakistan-India conflict, ZAB states: “The people of Pakistan want relations with India without entanglement. Confrontation which means neither peace nor war must be continued as a measure of self-defense until India realizes the need to settle all important disputes with Pakistan on the basis of recognized international merit and in a spirit of equality… It is an article of faith of the people of Pakistan that the day will come when the people of Jammu and Kashmir will link their destinies with Pakistan and that Pakistan’s other fundamental disputes with India, affecting the eastern parts of the country, would also find a just solution…. The roots of confrontation between India and Pakistan go deep into our history and will have to continue until the cause of justice triumphs, no matter how heavy the odds. Peace, denied to the six hundred million people of the sub-continent for centuries, can return only when the disputes are resolved. Peace, so necessary to eradicate poverty, ignorance, and disease, cannot come by the surrender of legitimate rights, but through their attainment. A policy of confrontation is not a policy of militarism; indeed, it often has the effect of averting a physical conflict. The only known means by which a nation can avoid military conflict is by total preparedness, not only in a military context.”

Commenting on freedom struggles of small nations, ZAB observes: “Small nations have always struggled against more powerful ones for their freedom. The whole history of mankind is a struggle of the oppressed against exploitation and domination. The contemporary history of Pakistan is nothing but an example of such a struggle. The struggle before Independence was against an alien racial domination; today it is for preserving independence. The wheel of change has come full circle, bringing us face to face with the same ancient menace. We are no more a subject people; we have the attributes of an independent nation and the will to remain free; though peace is our ideal, the defense of our rights continues to be the supreme objective of the people of Pakistan.”

In The Myth of Independence Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto (ZAB) champions the position that Pakistan must formulate its foreign policy on the basis of its own enlightened self-interest, uninfluenced by the transient global requirements of the Great Powers. The book is a mini-course in South Asian relations and history. It is a must read for general readers and students of history and international relations.

(Dr Ahmed S. Khan - dr.a.s.khan@ieee.org - is a Fulbright Specialist Scholar, 2017-2022).

“I am guiding you to seek truth from the facts of the historical conditions of our society and to identify the problems. The correct solutions will come with the correct identification of the problems.” — Zulfikar Ali Bhutto