Book & Author

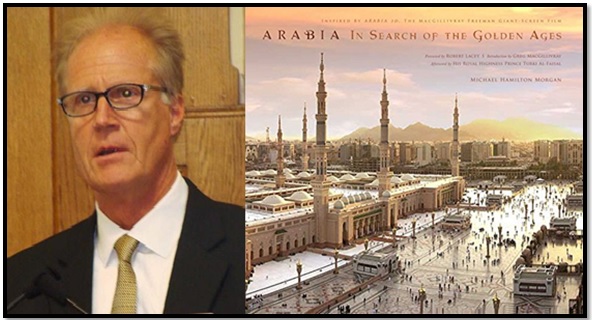

Michael Hamilton Morgan: Arabia — In Search of The Golden Ages

By Dr Ahmed S. Khan

Chicago, IL

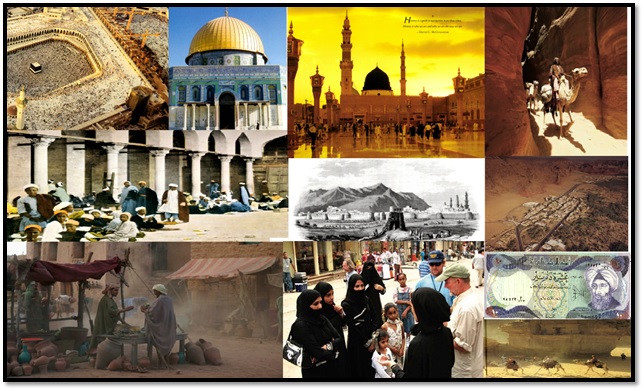

The Arabian peninsula — sheltered between the cradle of civilization and the busiest trade routes of the old world — is abode to millennia-old civilizations that have prospered in tough conditions. In Arabia — The Search of The Golden Ages former diplomat Michael Hamilton Morgan juxtaposes the progress of contemporary Saudi Arabia with its past golden age rich in culture and science. Morgan’s narrative is a companion coffee table book for the 2010 film Arabia 3D that chronicled the rich past and present of Saudi Arabia. The author advocates for appreciating the contributions made by the Muslim world — accomplished before the modern age — in the areas of medicine, mathematics, optics, chemistry, human anatomy, architecture and other domains.

Michael Hamilton Morgan, a former diplomat, has also authored Lost History, The Twilight War and co-authored with Robert Ballard Collision with History: The Search for John fir Kennedy's PT-109, and Graveyards of the Pacific. He created and heads New Foundations for Peace, which promotes cross-cultural understanding and leadership among youth.

In the foreword, describing Arabia, Robert Lacey, states: “Ancient and mysterious, Arabia has enthralled outsiders since the dawn of history. The spell first captured me more than thirty years ago when I went to live for a time in the historic town of Jeddah, the port for the pilgrim city of Makkah, beside the red sea. I was researching my book the kingdom, the story of the warriors and politicians of the House of Saud who struggled and schemed for over two and a half centuries to pull together the separate fragments of the peninsula and to stamp their identity upon them. Their struggle produced the Islamic kingdom of Saudi Arabia—today the premier oil power in the world and Arabia’s first major, unified national entity since the days when the teachings of the Prophet Mohammed [pbuh] inspired his followers to ride out across Europe and north Africa in the seventh century CE. Today the mystery endures... But the heart of Arabia remains foreign and intimidating to many people in the West. Folks just don't understand—and, to be honest, in some cases, they simply don't want to understand.”

Introducing Arabia, the author observes: “Although America and the world are deeply influenced by Arabia—and our influence has deeply penetrated into this other culture as well—we rarely understand the breadth and depth of our interaction. Most of us outsiders barely know this land and its people, beyond the superficial present—headlines, oil prices, accusations of extremism. The historical reality of Arabia is that this land—so often presented as a poor, isolated, and tribal backwater suddenly vaulted into wealth, modernity, and global influence— has played an influential role before. It happened two thousand years ago, when the Nabataeans built a kingdom based on the international spice trade with Rome and India. And fourteen hundred years ago, when Islam and Arabs poured out across half the globe, helping to trigger the European Renaissance as well as an annual global migration of Islamic pilgrims that continues until this day… Revelatory lands of Abraham, Moses, Jesus, Mohammed. For many people of faith, Arabia is indeed the center of the world—because their single greatest achievement will be to make the journey, if only once, to the holy cities of Makkah and Madinah.”

Reflecting on the Saudi-US relationship, in the foreword Prince Turk' al-Faisal, observes: “Understanding from the day king Abdul Aziz and President Roosevelt first met in February 1945, Saudi Arabia and the United States have had a mutually beneficial relationship. Understanding has been based on the strength of that initial person-to-person exchange. Since then, we've had our ups and downs, as they exist in all relationships. But we've helped each other when we could and in significant ways. Together, we successfully fought the spread of communism. Together, we stopped Iraqi aggression in Kuwait. For more than six decades, we were strong military allies, reliable energy partners, and good friends. But everything changed on September 11, 2001. That day, our relationship, which had lasted in calm for some sixty years, was plunged into crisis. Suddenly, there existed deep suspicion, mistrust, and misperception between our people. Any questions we may have had about each other became concerns. Any uncertainty became anxiety. Eight years later everything has been reexamined and the trust between our nations and our people is reestablished. And while our leaders can certainly make the necessary gestures, as King Abdul Aziz and President Roosevelt did, today diplomacy is not just the province of leaders… What you learn about Saudi Arabia in this book and what you see in MacGillivray Freeman's Arabia 3D film can be a start to this process of reestablishing and deepening our mutual understanding. But the real exchanges—the ones that form lasting bonds—need to be made in person. I encourage you, then, to take up this responsibility and use what you have encountered here as a basis for engaging with the world and assuming your role as a diplomat in your own right.”

Expounding on the ideas of institutions, leadership and coexistence, the author observes: “I've discovered that one particularly misunderstood area of commonality between Arab and Western culture is the subject of political leadership. Because Arab and Western worlds have evolved in different ways since 1500, their political institutions also seem very dissimilar. My research has shown that the disparity was not always so clear. During the Dark Ages, when Europe was mired in warlordism and anarchy after the fall of Rome, the Arab world—in particular the various Caliphates under Umayyad, Abbasid, and Fatimid leadership—was at its most politically cohesive and sophisticated. What is forgotten in the West is how much early Arab leaders influenced the Western ideal of good leadership. Charlemagne, the father of modern political Europe, was entranced with Harun Al Rashid and his style of leadership in Baghdad, even as he was trying to drive the Andalusian Arabs out of France. Saladin, the Muslim general who evicted the Crusaders from Jerusalem and broke European power in the Middle East, was seen by medieval Europeans as a magnanimous and great leader, praised by even the religiously partisan such as Dante Alighieri. Another area of positive Arab social influence is tolerance of diversity and religious coexistence. While the modern Western stereotype of Arab Muslim culture is that it is intolerant and exclusionary to the point of fanaticism, this was not always the case. Based on several passages in the Qur'an, the mainstream Muslim view is that the Prophet Mohammed [pbuh] urged his followers to give special protected status to the other two Abrahamic faiths, the Christians and Jews.”

Discussing Islam and enlightenment, the author notes: “It is 632 CE. The Prophet [pbuh] has only recently passed from this world, his followers still in shock and despair, but the story is only beginning. A shock wave of invention and social innovation has just been seeded by a talented but formally uneducated Arab man. The movement and culture he founded is about to overtake much older, richer, and more powerful cultures like those of Byzantium, Egypt and the Middle East, Spain, Central Asia, and North Africa—even India, the richest treasure house of them all. While conventional Western history points to Arab military conquest as the outcome of this cultural explosion, in my research I've found that answer doesn't hold up. I don't want to diminish the scope of the impromptu Arab military campaign in the century after the Prophet's death, from 632 until 732—when the Frankish general Charles Martel dealt the Arabs one of their few defeats, near Thurs, France. In just a hundred years, the Arab armies and their newfound allies had already poured across Arabia, Syria, Egypt and North Africa, and all of Iberia, and into southern France, across Sicily, all of Persia, deep into India, and far into Central Asia.”

Reflecting on the leadership role of Prophet Muhammed (pbuh) in shaping a dynamic society, the author states: “In my research, as I look back thirteen hundred years to a destitute and illiterate Europe, I realize Mohammed's [pbuh] progressive innovations in areas such as social charity, the empowerment of women, and protecting public health would allow his successors to begin all sorts of innovation and experimentation. The influence of the Prophet [pbuh] and the religion of Islam in creating a culture of science, humanitarianism, and problem-solving cannot be underestimated.”

On the leadership of Prophet Muhammed (pbuh), the author further observes: “The world today thinks of Mohammed [pbuh] as the father of Islam, the second most populous faith in the world, with its approximately 1.6 billion followers making it second in size only to Christianity. What few stop to realize—and what I have tried to emphasize in my writing and speaking over the last three years—is that Mohammed [pbuh] was also the father of one of the most powerful cultural, intellectual, and technological revolutions in human history—one that helped trigger modern technological civilization.”

Discussing the mechanism of finding the truth, the author quotes the words of great Arab Muslim philosopher, Al Kindi: “We ought not to be embarrassed about appreciating the truth and obtaining it from wherever it comes, even if it comes from races distant and nations different from us. Nothing should be dearer to the seeker of truth than the truth itself, and there is no deterioration of the truth, nor belittling either of one who speaks it or conveys it.”

Expounding on the idea of ‘the University and the Universe,’ the author observes: “I often argue that the very concepts of the modern university and the think tank were born in the Arab mind, as Muslims poured out across the world beginning in the seventh century CE. As far as we know, the world's first university, which like many grew out of the religious schools or madrassas attached to mosques, was Al Karaouine in Morocco, founded in 859 CE, followed soon after by Al Azhar in Cairo. Phenomenal, court-sponsored research centers began to be established, such as the eighth-century House of Wisdom founded by Caliph Harun Al Rashid in Baghdad and greatly expanded by his son Al Mamun, and the House of Knowledge in Cairo founded by the Fatimid Shiites who once ruled there. There were similar groups of court thinkers in Cordoba, Tunis, Palermo, Isfahan, Delhi, and Damascus. Their outpouring of knowledge was one of the greatest human achievements of all time. The vast intellectual and social revolution of the Arabs and Muslims was expressed in a thousand ways. But if I have to pick a starting place, it would be in the stars and in numbers. While they are now very separate disciplines, in the times of the early Arabs and their partners, astronomy and mathematics were one and the same. In fact, other disciplines like medicine, music, chemistry, and theology were all seen as the same subject.”

Reflecting on the similarities between the past and present Muslim intellectual capital, and achievements of Al Khwarizmi, the author observes: “I see great similarities between the engineers and scientists building the future departments and research programs at KAUST and the hundreds of Arab Muslim astronomer-mathematicians working across the vast Muslim world a thousand years ago, many of whom would surely qualify for Nobel Prizes today. But if I have to pick out just one forgotten thinker to recognize, it would be a man of hazy origins in the early ninth century, who emigrated from Khiva in eastern Persia to Baghdad to work in Caliph Al Mamun's House of Wisdom. His name was Mohammed Al Khwarizmi, and I believe he had more practical impact on our everyday lives than did modern geniuses like Albert Einstein or Sir Isaac Newton. Because of his breakthroughs in geography, astronomy, cartography, and algebra—and its offspring, the algorithm—more than any man he could be called the father of modern computation, software, and the digital world. His work helped to spread Hindu-Arabic numerals throughout Europe, and later translations of his work introduced to the West our modern decimal system. Summed up, Al Khwarizmi lifted mathematics beyond the Greek ‘earth measurement’ known as geometry into pure abstraction. In abstraction there was an infinite potential for invention. For centuries Western mathematicians thought that the word ‘algorithm’ was from the Greek, reflecting their own bias and their unfamiliarity with Arabic. But it was recently rediscovered that the Latin word algoritmi was really a rendering of Al Khwarizmi's name. The algorithm is the language of modern software and computation, of computer encryption and financial market modeling, and of Google searches. It is one of the mathematical foundations of the digital world.”

Discussing the work of Jabir Ibn Hayyan, the author notes: “The planners at KAUST are developing research programs in chemical science and chemical engineering to rank with the greatest research programs in the world… But what few remember is that the very concept of chemistry was shaped in the forgotten Arab past. The father of modern chemistry was Jabir Ibn Hayyan, an eccentric and secretive man of Yemeni heritage who worked in late eighth-century Baghdad. He worked for Caliph Harun Al Rashid, and he was equally drawn to the magical possibilities of matter and to the hard realities of chemical and physical reactions. In fact, he was also the first modern alchemist, before the study of matter had separated into magic and hard science.”

Expounding on the discoveries of Ibn Al Haytham in the domains of optics, the author states: “…actually tested the theory and found…light was emitted from a light source, traveled to the object, and was reflected to the eye, where it was perceived. This Iraqi Arab gave us the first modern understanding of the human eye and its connection to the brain. He explained the refracting power of the lens. He invented the camera obscura about five hundred years before Leonardo da Vinci documented and described its uses. He proved that light travels in straight lines. He gave us the first mathematical calculation of that mystical state known as twilight, which for Ibn Al Haytham was really a function of angle and shadow, occurring when the sun was 19 degrees below the horizon. Though all these discoveries seem unsurprising, given our current knowledge, Ibn Al Haytham was the first to make and document them. His discoveries opened the door for later revolutionary work by European explorers of the heavens such as Galileo and Copernicus. In fact, a present-day theory called the Hockney-Falco thesis postulates that Ibn Al Haytham may have influenced the mechanical optical aids used by Renaissance artists, which enabled them to develop important techniques such as atmospheric perspective, where distant objects appear to be more hazy than those nearby, a classic breakthrough of Renaissance painters like Leonardo.”

Reflecting on the accomplishments of Muslim scientists in the field of medicine, the author notes: “But I find the recent perception of the backwardness of Saudi medicine is misleading, because in my research I've found that the early Arabs and their Muslim partners did more to create modern medicine than any other group, with the exception of contemporary Western civilization. Arab Muslim medical innovation was no accident; while it depended on very smart innovators from many lands, it was spawned by certain teachings of the faith. While medieval Christian medicine was limited by grinding European poverty, an anti-intellectual bent…Muslim medicine had different values. The Prophet [pbuh] himself had told his followers how to use quarantine as a way to limit the spread of disease. He had spoken on such subjects as personal hygiene, diseases like mange and venereal infection, and the process of reproduction. These medical conditions were not seen as the wages of sin or as divine punishment, but rather physical problems to be understood and, if necessary, solved.”

Discussing observations of the critics of Islamic civilization, the author notes: “I've had very well-educated and open-minded people assert to me that Islamic civilization was and is intellectually dead, and only survived by stealing the ideas of others. I've had them tell me it is utterly alien to all invention, creativity, and individualism. Given current global stereotypes and the Western media's focus on crisis and underdevelopment in the Muslim world—and our very incomplete world history curricula in America—this is no surprise.”

Expounding on the reasons why scholars in the West have ignored the contributions of Islamic civilization, the author states: “What I've tried to do in my work is to understand and explain why Westerners continue to ignore the contributions of this vast civilization. I've argued that part of the reason is that much of the Arabic innovation happened a thousand years ago and so has been forgotten. But I believe it was compounded by the fact that the Christian West, deeply infatuated with Greco-Roman culture, was always very hostile to the faith of Islam, fearing it would overthrow Christianity—and so the culture of Arabs, Persians, Indians, Africans, Asians, and indigenous Americans were seen as 'primitive' and 'pre-modern,’ and their cultural contributions were judged to be implicitly inferior. I've found that there was even an echo-chamber effect from the European colonialist narrative among Arabs and Muslims. Ironically, as European political, financial, and cultural dominance swept the globe in the form of colonialism, many cultures that had experienced a great Islamic influence—in India, the Arab Middle East, and parts of Africa—came under European control, and they ended up learning their own history from European educational systems. And so many Muslim societies absorbed the same Western story of themselves—and its implicit conclusion that there was an inferiority and dysfunction to Muslim culture.”

To conclude the book, the author notes: “Even as the world has come into Arabia and changed it, and has been changed by it, some things are eternal. Aside from the unchanging vastness of the desert and the searing sky above, the other constant in the modern Saudi landscape is the enduring faith of Islam, and its architectural expression, the mosque. But the stereotype of an Arabia forever isolated and apart is obviously untrue. While the intervals of exchange may have been broken by long periods of separation, the legacy of the connections is just as strong as the results of the isolation…Might Arabia have looked different today, had the second golden age happened here in the Kingdom, and not in faraway places like Baghdad, Cordoba, Delhi, and Samarkand? Almost certainly it would have. But once again, landscape, climate, and trade patterns meant that, except in the religious sphere, the greatest flowering of Arab Muslim civilization happened outside the peninsula. The irony of the second Arab golden age was that it had more impact on the outside world than on Arabia itself.”

In Arabia — The Search of The Golden Ages Michael Hamilton Morgan introduces readers to the dynamics of contemporary Saudi Arabia and its past — rich in culture and scientific achievements —viz a viz medicine mathematics, human anatomy, optics, chemistry, architecture and other domains. The book contains exquisite photos of people, mosques, terrain, desert and important landmarks of the cities of Mecca, Madinah, Jeddah, Riyadh, and Dhahran. It is a must read for all general readers and students of anthropology, religion, and history of science and technology.

Dr Ahmed S. Khan ( dr.a.s.khan@ieee.org ) is a Fulbright Spiciest Scholar (2017-2022).