Book & Author

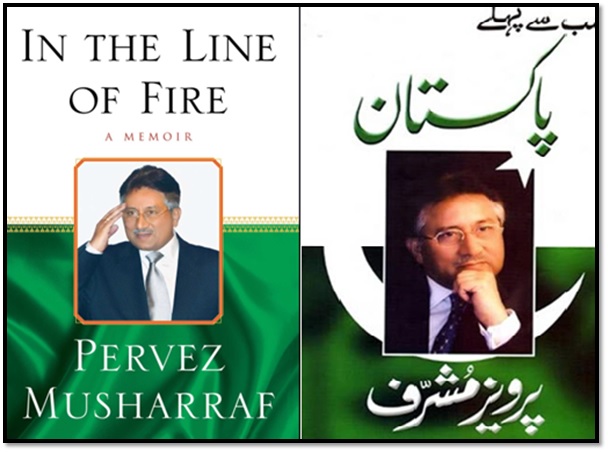

Pervez Musharraf: In Line of Fire — A Memoir

By Dr Ahmed S. Khan

Chicago, IL

General Pervez Musharraf narrates his life story — migration to Pakistan, military career, role in 1965, 1971 and Kargil wars, becoming an accidental dictator due to blunders of Sharif family, role in economic revival and war on terror — in a simple but absorbing manner

“Leaders of nations have a much larger overall responsibility: to motivate their people and their nation, inspiring them, infusing confidence into them, and generating in them a spirit and urge to perform…The leader must have the will to change public opinion in the true national interest.”

Former President General Syed Pervez Musharraf (b. August 11, 1943 , Delhi, British India) passed away at the age of 79, on February 5, 2023, in Dubai, UAE, after a prolonged amyloidosis ailment. His funeral prayers were offered at Malir Cantonment on February 7, 2023, and his body was laid to rest at a military graveyard near Kala Pul in Karachi.

General Pervez Musharraf leaves behind a controversial legacy of his tenure (October 12, 1999 – August 18, 2008): his admirers highlight his major accomplishments — liberalization of media, revival of economy, empowerment of women, establishment of accountability and policy-making institutions, revamping of the local government system, strengthening of armed forces, and development of mega infrastructure projects; his critics point out his mega blunders — 1999 coup, suspension of constitution, imposition of emergency, giving NRO to corrupt politicians, sacking of Chief Justice, killing of Sardar Akbar Bugti, belittling of Dr Abdul Qadeer Khan, attenuation of societal and religious values via “enlightened Moderation,” May 12, 2007 riots in Karachi, selling off innocent Pakistanis for dollars, Red Mosque operation, immense human and financial losses to the country due to extraconstitutional decisions by one-man rule, lack of accountability and promotion of moral and financial corruption in armed forces viz a viz “ Women & Wine” and “ Real Estate (plots)” culture.

In the Line of Fire — A Memoir General Pervez Musharraf (GPM) narrates his struggles in the domestic and international domains — his family’s migration to Pakistan, early days in Karachi and Turkey, joining army, coming to power on October 12, 1999, as an accidental dictator, confrontation with India in Kashmir (Kargil), and role in post-9/11 war on terror. The book’s Urdu version is titled: Sub Say Pahlay Pakistan.

GPM dedicates the book to the people of Pakistan and his mother. The book has six parts with thirty-two chapters spanning 338 pages. Part-I covers stories of migration to Pakistan, settling in Karachi and going to Turkey, Part-II focuses on life in the Army, Part-III narrates the background of the 1999 coup, Part-IV presents the details of the quest for democracy and kick-starting the economy, Part-V describes the pre- and post-9/11 world and war on terror, and Part-VI sheds light on an array of topics — nuclear proliferation, diplomacy, social sector, emancipation of women, soft image of Pakistan and the Leadership on Trial: The Earthquake.

Reflecting on the purpose of the book, in the preface GPM observes: “This book is a window into contemporary Pakistan and my role in shaping it. I have lived a passionate life, perhaps an impetuous one in my early years, but always I have focused on self-improvement and the betterment of my country. Often, I have been chastised for being too forthright and candid, and I trust you will find these qualities reflected here. I do not shy away from sensitive issues, circumscribed only by certain dictates of national security. I decided to write my autobiography after Pakistan took center stage in the world's conflicts, including the war on terror. There has been intense curiosity about me and the country I lead. I want the world to learn the truth…Governing Pakistan has been labeled by some as one of the most difficult jobs in the world. September 11, 2001, multiplied Pakistan's challenges many times over, amplifying domestic issues, and reshaping our international relations.” Remembering his migration to Pakistan in August 1947, GPM states: “On a hot and humid summer day, a train hurtled down the dusty plains from Delhi to Karachi. Hundreds of people were piled into its compartments, stuffed in its corridors, hanging from the sides, and sitting on the roof. There was not an inch to spare. But the heat and dust were the least of the passengers' worries. The tracks were littered with dead bodies — men, women, and children, many hideously mutilated. The passengers held fast to the hope of a new life, a new beginning in a new country — Pakistan — that they had won after great struggle and sacrifice. Thousands of Muslim families left their homes and hearths in India that August, taking only the barest of necessities with them. Train after train transported them into the unknown. Many did not make it — they were tortured, raped, and killed along the way by vengeful Sikhs and Hindus.”

Reflecting further on the migration, GPM notes: “This is the story of a middle-class family, a husband and wife who left Delhi with their three sons. Their second-born boy was then four years and three days old. All that he remembered of the train journey was his mother's tension. She feared massacre by the Sikhs. Her tension increased every time the train stopped at a station, and she saw dead bodies lying along the tracks and on the platforms. The train had to pass through the whole of the Punjab, where a lot of killings were taking place. The little boy also remembered his father's anxiety about a box that he was guarding closely. It was with him all the time. He protected it with his life, even sleeping with it under his head, like a pillow. There were 700,000 rupees in it, a princely sum in those days. The money was destined for the foreign office of their new country.”

Tracing his family’s roots and background, GPM states: “My father, Syed Musharrafuddin, and his elder brother graduated from the famous Aligarh Muslim University…My father joined the foreign service as an accountant. He ultimately rose to the position of director. He died just a few months after I took the reins of my country…Khan Bahadur Qazi Fazle Ilahi, my mother’s father, was a judge…he was progressive, very enlightened in thought, and quite well off. He spent liberally on the education of all of his sons and daughters. My mother Zarin graduated from Delhi University and earned a master’s degree from Lucknow University at a time when few Indian Muslim women ventured out to get even a basic education. After graduation, she married my father and shifted to Nehar Wali Haveli [Delhi].”

Reflecting on the economic struggles of his parents, GPM recalls: “My parents were not very well off, and both had to work to make ends meet, especially to give their three sons the best education they could afford. The house was sold in 1946, and my parents moved to an austere government home built in a hollow square at Baron Road, New Delhi. We stayed in this house until we migrated to Pakistan in 1947.”

Commenting on the initial hardships faced in Pakistan, GPM observes: “My mother became a schoolteacher to augment the family income. My parents were close, and their shared passion was to give their children the best possible upbringing --- our diet, our education, and our values. My mother walked two miles (more than three kilometers) to school and two miles back, not taking a tonga (a horse-drawn carriage), to save money to buy fruit for us. We always looked forward to that fruit. Providing a good education to our children has always remained the focus of our family, a value that both my parents took from their parents and instilled in us. Though we were not by any means rich, we always studied in the top schools.”

Remembering the kind heartedness of his mother, GPM recalls one incident that took place in 1949 while his family was living in Jacob Lines barracks: “One night I saw a thief hiding behind the sofa in our apartment. Though I was only a little boy, I was bold enough to quietly slip out to my mother, who was sleeping on the veranda (my father had left for Turkey). I told her that there was a thief inside, and she started screaming. Our neighbors assembled. The thief was caught with the only value we had — a bundle of clothes. While he was being thrashed, he cried out that he was poor and very hungry. This evoked such sympathy that when the police came to take him away, my mother declared that he was not a thief and served him a hearty meal instead. It was a sign of the sense of accommodation and helping each other that we shared in those days.”

Commenting on the generous nature of his father, GPM states: “My father was a very honest man, not rich at all, but he would give money to the poor — ‘because their need is greater.’ This was a point of contention with my mother, who was always struggling to make ends meet. ‘First meet your own needs before meeting the needs of others.’ She would tell him. Like most Asian mothers, despite their demure public demeanor, my mother was the dominant influence on our family. But on the issue of giving to the needy my father always got his way, because he wouldn’t talk about it.”

Reflecting on his mother’s efforts to support the family, GPM observes: “My mother had to continue working to support us. Instead of becoming a schoolteacher again, she joined the customs service. I remember her in her crisp white uniform going to Korangi Creek for the arrival of the seaplane, which she would inspect. I also remember that she once seized a cargo of smuggled goods and was given a big reward for it.”

Reminiscing about family’s return to Karachi from Turkey, GPM states: “In October 1956, when I was thirteen years old, we arrived back in Karachi…My father reported back to the foreign office…We found a house [Darussalam] in Nazimabad Block 3, one of many new settlements that had mushroomed after independence to accommodate millions who had fled India…My mother soon found another job [at Philips in SITE]…Our neighborhood, Nazimabad, was a tough place to live…A boy had to be street-smart to survive…I was one of the tough boys.”

Indeed, Pervez was a tough kid, his chums, Manzoor and Ijaz recall that in case of a fight between rival groups of boys, Pervez was always called upon to resolve the conflict. His modus operandi was very straight forward — first he would try to request the aggressors’ lead boy to realize his mistake and resolve it peacefully, but if the kid did not listen to Pervez’s advice and get into fighting mode, Pervez would launch a punch with lightning speed on the boy’s face forcing him to run away. That was Pervez’s first lesson in conflict resolution in Nazimabad!

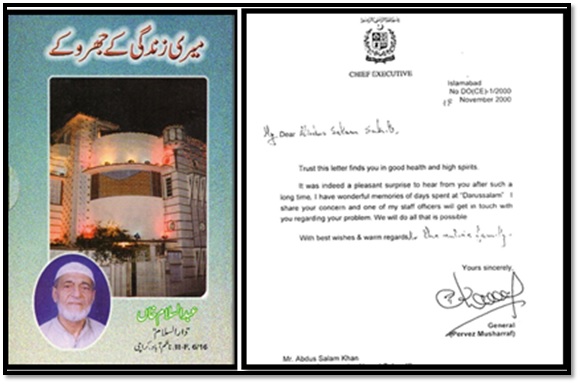

While living at Darussalam, Nazimabad, Begum Zarin guided her sons for a very disciplined life. During the weekdays parents and kids were busy with their jobs and school routines. On weekends, Zarin Aappa, as owners of Darussalam (Mrs Abdus Salam Khan, whom Zarin Aappa used to call Chottee Bahoo) recall, would make sure that all members of the household participate in house cleaning activities before taking their breakfast in the morning. Zarin Aappa understood the personal habits and aptitudes of her sons, so she advised eldest son Javed to pursue civil service, Pervez (whom she called by nickname Palloo) to join the Army and the youngest son Naved to become a doctor. The Musharraf family enjoyed their stay at Darussalam very much. Fifty years after their stay at Darussalam, whenever Javed and Pervez were in Karachi, they used to visit Darussalam; they had very fond memories of this house where they had spent their childhood. When Pervez Musharraf became president, in a letter to the owner of Darussalam, Mr Abdus Salam Khan, he expressed his fond memories of Darussalam. The owners of Darussalam also have fond memories of Zarin Aappa’s nafees (refined) personality.

Commenting on the reading habit of his elder brother Javed, GPM notes: “Javed was very fond of books, but I read them only when I had to. We became members of the British Council Library and would take out our weekly quota of two books each. Being a voracious reader, Javed would finish his books in a couple of days and then read my books in the next two — if not sooner! Before the week was up, he would want to return to the library and take out four more books. I had perhaps read one, or not even that. So, I would insist that we wait until the end of the week, after which I would want to renew one of the books and take out only one new one. This would upset Javed and lead to arguments.”

Remembering a battle of the 1965 War, GPM observes: “On the night of September 22, our guns were positioned in a graveyard. An enemy shell hit one of our self-propelled artillery guns and set its rear compartment on fire. The flames leaped up toward the sky in the darkness of the night. The ready-to-fire shells on the gun were in danger of catching fire and bursting, setting off a chain reaction with all the other guns. It was a very dangerous situation. ‘Hell!’ I thought. ‘My gun battery could be blown to pieces, taking all of us along.’ I had to act immediately; there was no time to lose. While everybody took cover, a lesson that I had learned on the streets of Nazimabad, came into play. I stood my ground, dashed to the blazing gun, and climbed into it. One brave soldier followed me. We saw three men of the crew lying in a pool of blood. Instinctively, I ignored them, in order to save the shells first. We took off our shirts and wound them around our hands for protection from the hot shells. One by one we took the shells off the gun and threw them to safety on the ground, hoping that they would not burst on impact. God saved us from that disaster. In the meantime, seeing me facing all this danger, all my men who had run for cover returned…The brave soldier who helped me was also decorated for gallantry. I can never forget that night.”

Reflecting on the fall of East Pakistan, GPM states: “What happened in East Pakistan is the saddest episode in Pakistan's history. The loss of our eastern wing and the creation of Bangladesh were all a result of inept political handling ever since our independence. Blame ultimately fell on the army. As events developed, the army was confronted with an impossible situation — a mass popular uprising within and an invasion from without by India, supposedly nonaligned but now being helped overtly by the Soviet Union under a treaty of peace and friendship. It was actually an alliance of war. On the other hand, our longtime ally, the United States of America, apart from making sympathetic noises and wringing its hands, was nowhere to be seen. No army in the world can sustain such a multidimensional threat. Nonetheless, the operational handling of the troops by the army's senior leadership was simply incompetent. It brought avoidable disgrace to the army. A cease-fire was declared on December 17, 1971, and Pakistan was cut in half.”

Commenting on the personality of Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, GPM notes: “At first, I admired Bhutto. He was young, educated, articulate, and dynamic. He had eight years' experience in government under President Ayub Khan. But as time passed, my opinion of Bhutto started to change. My brother Javed, who was principal secretary to the chief minister of the North-West Frontier province, told me that Bhutto was no good and would ruin the country. My brother was right. I saw how the country, and particularly its economy, was ravaged by mindless nationalization. Its institutions were destroyed under his brand of so-called Islamic socialism. Bhutto took control of virtually all the nation's industries — steel, chemicals, cement, shipping, banking, insurance, engineering, gas and power distribution, and even small industries like flour milling, cotton ginning, and rice husking, as well as private schools and colleges — the start of the destruction of our educational system. Mercifully, he did not touch textiles, our largest industry. Bhutto ruled not like a democrat but like a despotic dictator.”

Remembering Pakistani troops’ outstanding performance in Somalia on UN peacekeeping mission, GPM notes: “Regrettably, the film Black Hawk Down ignores the role of Pakistan in Somalia. When US troops were trapped in the thickly populated Madina Bazaar area of Mogadishu, it was the Seventh Frontier Force Regiment of the Pakistan Army that reached out and extricated them. The bravery of the US troops notwithstanding, we deserved equal, if not more, credit; but the filmmakers depicted the incident as involving only Americans.”

Reflecting on a noble deed by the Pakistani troops on the UN mission in Bosnia, GPM states: “I was detailed to go to Bosnia to decide on the commitment and deployment of the Pakistani Brigade. I flew in with a small team of four officers. We reached Sarajevo in a UN helicopter…I was strolling around the compound of the palace with the commanding officer, a colonel, of my host Egyptian battalion, I heard a distinct sound of whining from outside. I asked what it could be. The colonel knew what it was and said it was quite a regular feature every night. He took me to the main entrance gate. There were some dozen or two dozen children, begging and crying for food. My eyes swelled with tears, both at their misery and at my helplessness to assist them. I gave them all the dollars I was carrying and turned back, full of pain and sorrow. When the Pakistani Brigade group of three battalions finally came, all its personnel fasted one day of every week, and distributed the food they had saved among the more needy Bosnians. It was taken as a noble gesture by the populace.”

Commenting on the financial challenges and economic revival, GPM observes: “In 1999…The dreaded words ‘failed state’ were on everyone's lips. That is a distant memory now. The economy is on an upsurge. Our gross domestic product (GDP) has risen from $65 billion to $125 billion— almost double in five years— and we now are in a different league altogether. International financial institutions look on us very differently and with respect. The growth in GDP rose from 3.1 percent to a healthy 8.4 percent in 2005. We will achieve 7 percent in 2006 in spite of the negative effect of rising oil prices and the reconstruction effort following the earthquake. Our overall foreign debt has been reduced from $39 billion to $36 billion.”

Describing his work habit, GPM states: “In my first year in office— the year 2000—1 put in over fifteen hours a day at work. I used to leave home about at nine am, work the first shift till around six pm, return for a shower and a change of clothes, receive some working group or other at seven pm at home, continue with them till about ten pm (with or without dinner), and finally receive another working group at around eleven PM, to continue till around two am. This routine remained constant for over a year. In these sessions through sheer hard work, we evolved strategies for many elements of governance that had simply been nonexistent. I realized then how the state was being run on a day-to-day basis in a directionless manner. It was also through these laborious sessions that I learned all I did not know, especially about the economy.”

Reflecting on the future of the country, GPM observes: “Pakistan still has a long way to go. We have made great progress, but we cannot rest. With determination, persistence, and honest patriotic zeal, God willing, we will become a dynamic, progressive, and moderate Islamic state, and a useful member of the international comity of nations — a state that is a model to be emulated, not shunned.”

In Line of Fire — A Memoir by Pervez Musharraf is an interesting read. General Pervez Musharraf narrates his life story — migration to Pakistan, military career, role in 1965, 1971 and Kargil wars, becoming an accidental dictator due to blunders of Sharif family, role in economic revival and war on terror — in a simple but absorbing manner. The book is essential reading for all students of history, international relations, and especially for all civilian and military officers of Pakistan so that they can learn from GPM’s blunders, and benefit from his insights on leadership and diplomacy.