Book & Author

Professor Edward Said: Covering Islam — How The Media And The Experts Determine How We See The Rest of The World

By Dr Ahmed S. Khan

Chicago, IL

"Covering Islam should be read by every foreign correspondent and every editor of foreign news.... Edward Said shows that the American press has invented fiction for itself called `Islam; something like the American picture of `Communism' in the 1950s....Said’s analysis is cool and persuasive. He is no apologist for anyone. This is an important book.” - Frances FitzGerald, Author of Fire in the Lake, and America Revised

Covering Islam — How The Media And The Experts Determine How We See The Rest of TheWorld by Professor Edward Said first published in 1981, in the backdrop of a series of events — Iranian revolution, the hostage crisis, and the energy shortages — shows how Islam became the main news. Professor Said, using a very methodical approach presents his analysis about how in the West, academic experts, corporate and governmental policymakers, and the media see "Islam" as representing everything from anti-Americanism to good business to an inferior culture, a dangerously enthusiastic religion, and bad values. Especially in today’s environment of “Islamophobia” and “Fake News,” Professor Said’s scholarly work has become even more timely than it was in the early 1980s. His narrative and analysis both refresh our memory, as well as serve to highlight how severely the news media has continued to obscure and distort the realities about the Middle East, Arabs, Muslims, and Islam.

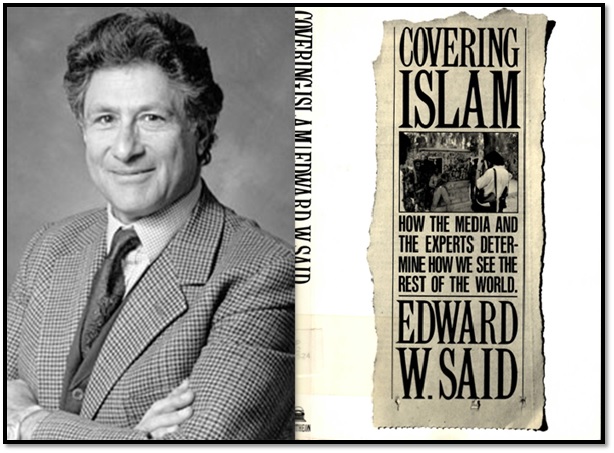

Edward W. Said (1935, Jerusalem, Mandatory Palestine -2003, New York, USA) was an academic, political activist, and the most distinguished literary critic who analyzed literature in the context of social and cultural politics. He attended lower and secondary schools in Jerusalem and in Egypt. He came to the United States for higher education and received his BA from Princeton, and his MA and PhD from Harvard, where he won the Bowdoin Prize. In 1974 he was Visiting Professor of Comparative Literature at Harvard, and during 1975-76 was a fellow at the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences at Stanford. In 1977 he delivered the Gauss Lectures in Criticism at Princeton, and in 1979 he was Visiting Professor of Humanities at Johns Hopkins. Later, he served as Parr Professor of English and Comparative Literature at Columbia University. His work has been translated into eight languages and published throughout Europe, Africa, Asia, and Australia. His book Beginnings: Intention and Method won the first annual Lionel Trilling Award, given at Columbia University. In 1978 his book Orientalism was a runner-up in the criticism category of the National Book Critics Circle Award. His other notable titles include The World, the Text, and the Critic, After the Last Sky, Culture and Imperialism, Out of Place, and The Question of Palestine.

In Covering Islam Professor Said presents his analysis in three chapters. The first chapter Islam as News, reveals how the Middle East remains unknown to majority of Americans, except as it is tied to newsworthy topics like oil and terrorism; how news media distorts and obscures the realities about Muslims and Arabs by labelling them as oil suppliers or terrorists; how newsworthy issues are selected not by considering American national interests, rather by the special groups with specific interests, like energy corporations, Zionists, etc. Chapter two The Iran Story narrates the West’s response to the Iranian Revolution and the overthrow of Shah Pahlavi. And chapter three Knowledge and Power, shows how the West uses knowledge to project its power viz a viz using scientific tools of quasi-objective representation to distort and misrepresent Islam.

In the Introduction, the author reflecting on the objectives of writing about the relationship between the Orient and the Occident, states: “This is the third and last in a series of books in which I have attempted to treat the modem relationship between the world of Islam, the Arabs, and the Orient on the one hand, and on the other the West, France, Britain, and in particular the United States. Orientalism is the most general; it traces the various phases of the relationship from the Napoleonic invasion of Egypt, through the main colonial period and the rise of modem Orientalist scholarship in Europe during the nineteenth century, up to the end of British and French imperial hegemony in the Orient after World War II and the emergence then and there of American dominance. The underlying theme of Orientalism is the affiliation of knowledge with power. The second book, The Question of Palestine, provides a case history of the struggle between the native Arab, largely Muslim inhabitants of Palestine and the Zionist movement (later Israel), whose provenance and method of coming to grips with the ‘Oriental’ realities of Palestine are largely Western. More explicitly than in Orientalism, my study of Palestine attempts also to describe what has been hidden beneath the surface of Western views of the Orient—in this case, the Palestinian national struggle for self-determination. In Covering Islam my subject is immediately contemporary: Western and specifically American responses to an Islamic world perceived, since the early seventies, as being immensely relevant and yet antipathetically troubled, and problematic. Among the causes of this perception has been the acutely felt shortage of energy supply, with its focus on Arab and Persian Gulf oil, OPEC, and the dislocating effects on Western societies of inflation and dramatically expensive fuel bills.”

About the portrayal of Islam in the West, the author observes: “One of the points I make here and in Orientalism is that the term ‘Islam’ as it is used today seems to mean one simple thing but in fact is part fiction, part ideological label, part minimal designation of a religion called Islam. In no really significant way is there a direct correspondence between the "Islam" in common Western usage and the enormously varied life that goes on within the world of Islam, with its more than 800,000,000 people, its millions of square miles of territory principally in Africa and Asia, its dozens of societies, states, histories, geographies, cultures. On the other hand, ‘Islam’ is peculiarly traumatic news today in the West, for reasons that I discuss in the course of this book. During the past few years, especially since events in Iran caught European and American attention so strongly, the media have therefore covered Islam: they have portrayed it, characterized it, analyzed it, given instant courses on it, and consequently they have made it ‘known.’ But, as I have implied, this coverage—and with it the work of academic experts on Islam, geopolitical strategists who speak of ‘the crescent of crisis,’ cultural thinkers who deplore ‘the decline of the West’ —is misleadingly full. It has given consumers of news the sense that they have understood Islam without at the same time intimating to them that a great deal in this energetic coverage is based on far from objective material. In many instances ‘Islam’ has licensed not only patent inaccuracy but also expressions of unrestrained ethno-centrism, cultural and even racial hatred, deep yet paradoxically free-floating hostility. All this has taken place as part of what is presumed to be fair, balanced, responsible coverage of Islam. Aside from the fact that neither Christianity nor Judaism, both of them going through quite remarkable revivals (or ‘returns’), is treated in so emotional a way, there is an unquestioned assumption that Islam can be characterized limitlessly by means of a handful of recklessly general and repeatedly deployed clichés….On the other hand, ‘Islam’ has always represented a particular menace to the West, for reasons I discussed in Orientalism and re-examine in this book. Of no other religion or cultural grouping can it be said so assertively as it is now said of Islam that it represents a threat to Western civilization. It is no accident that the turbulence and the upheavals which are now taking place in the Muslim world (and which have more to do with social, economic, and historical factors than they do unilaterally with Islam) have exposed the limitations of simple-minded Orientalist clichés about ‘fatalistic’ Muslims without at the same time generating anything to put in their place except nostalgia for the old days, when European armies ruled almost the entire Muslim world, from the Indian subcontinent right across to North Africa. The recent success of books, journals, and public figures that argue for a reoccupation of the Gulf region and justify the argument by referring to Islamic barbarism is part of this phenomenon.”

Pointing to the conflict of interest of the so-called ‘Experts’ on Islam who fabricate ‘the truth’ according to needs, the author states: “At the very same time there is scarcely an expert on ‘Islam’ who has not been a consultant or even an employee of the government, the various corporations, the media. My point is that the cooperation must be admitted and taken into account, not just for moral reasons, but for intellectual reasons as well. Let us say that discourse on Islam is, if not absolutely vitiated, then certainly colored by the political, economic, and intellectual situation in which it arises: this is as true of East as it is of West. For many evident reasons, it is not too much of an exaggeration to say that all discourse on Islam has an interest in some authority or power. On the other hand, I do not mean to say that all scholarship or writing about Islam is therefore useless. Quite the contrary; I think it is more useful than not, and very revealing as an index of what interest is being served. I cannot say for sure whether in matters having to do with human society there is such a thing as absolute truth or perfectly true knowledge; perhaps such things exist in the abstract—a proposition I do not find hard to accept—but in present reality truth about such matters as ‘Islam’ is relative to who produces it.”

Citing an example of the competition between the print and electronic media in generating news about Iran, the author observes: “The competition between print and images has made for overemphasis on what is bizarre in Shi'a Islam and for psychological profiles of Khomeini, although the same competition accounts for neglect in coverage of other figures and forces at work in Iran. Still more important—and distorting—is the fact that the media have been used as diplomatic conduits, an aspect of ‘the Iran story’ noted thoughtfully by Broadcasting magazine on December 24, 1979. The Iranians as well as the United States government were perfectly aware that statements made on television were aimed not only at people who wanted the news but also at governments, at partisans of one faction or another, at new or emerging political constituencies. No one has studied the effect of this on ‘deciding what's news,’ but I believe that a general awareness of it drove United States reporters to think restrictively and reductively in us-versus-them dichotomies. Yet this literalization of group feeling made the reporters' incapacities and inaccuracies more rather than less apparent.”

Discussing Knowledge and power viz a viz the politics of interpreting Islam (Orthodox and Antithetical Knowledge), the author identifies three groups: young scholars (more sophisticated and honest politically), older scholars (whose work runs counter to orthodox scholarship), and writers, activists, and scholars (who are not accredited experts on Islam but whose role in society is determined by their overall oppositional stance). And about these groups, makes the following observation: “What is most important, in my opinion, about these three groups is that for them knowledge is essentially an active sought out and contested thing, not merely a passive recitation of facts and ‘accepted’ views. The struggle between this view as it bears upon other cultures and beyond that into wide political questions, and the specialized institutional knowledge fostered by the dominant powers of advanced Western society is an epochal matter. It far transcends the question whether Knowledge and Power view is pro- or anti-Islamic, or whether one is a patriot or a traitor. As our world grows more tightly knit together, the control of scarce resources, strategic areas, and large populations will seem more desirable and more necessary. Carefully fostered fears of anarchy and disorder will very likely produce conformity of views and, with reference to the "outside" world, greater distrust: this is as true of the Islamic world as it is of the West. At such a time—which has already begun—the production and diffusion of knowledge will play an absolutely crucial role. Yet until knowledge is understood in human and political terms as something to be won to the service of coexistence and community, not of particular races, nations, classes, or religions, the future augurs badly.”

Discussing the interpretation of knowledge by various entities, the author observes: “My thesis in this book has been that the canonical, orthodox coverage of Islam that we find in the academy, in the government, and in the media is all interrelated and has been more diffused, has seemed more persuasive and influential, in the West than any other ‘coverage’ or interpretation. The success of this coverage can be attributed to the political influence of those people and institutions producing it rather than necessarily to truth or accuracy. I have also argued that this coverage has served purposes only tangentially related to actual knowledge of Islam itself. The result has been the triumph not just of a particular knowledge of Islam but rather of a particular interpretation which, however, has neither been unchallenged nor impervious to the kinds of questions asked by unorthodox, inquiring minds.”

Reflecting further on the interpretation of knowledge, the author states: “… all knowledge is interpretation, and that interpretation must be self-conscious in its methods and its aims if it is to be vigilant and humane, if it is also to arrive at knowledge. But underlying every interpretation of other cultures—especially of Islam —is the choice facing the individual scholar or intellectual: whether to put intellect at the service of power or at the service of criticism, community, and moral sense. This choice must be the first act of interpretation today, and it must result in a decision, not simply a postponement. If the history of knowledge about Islam in the West has been too closely tied to conquest and domination, the time has come for these ties to be severed completely. About this one cannot be too emphatic. For otherwise we will not only face protracted tension and perhaps even war, but we will offer the Muslim world, its various societies and states, the prospect of many wars, unimaginable suffering, and disastrous upheavals, not the least of which would be the birth of an ‘Islam’ fully ready to play the role prepared for it by reaction, orthodoxy, and desperation. By even the most sanguine of standards, this is not a pleasant possibility.”

In Covering Islam — How The Media And The Experts Determine How We See The Rest of The World, Professor Edward Said has eloquently summarized various intrinsic and extrinsic cultural biases, religious prejudices and the moral and ethical bankruptcy of the news media, the roots of which he traces to collaboration of academia-corporate-government network that excels in distorting facts, obscuring reality and reverse engineering the news for achieving specific outcomes. It is an essential reading for all students of journalism, international affairs, history, all who are in the news industry! In today’s AI dominated information domains saturated with Islamophobia and Fake News, all seekers of truth and wisdom truly miss scholars like Professor Edward Said!

(Dr Ahmed S. Khan - dr.a.s.khan@ieee.org - is a Fulbright Specialist Scholar)