In Pugnacious Pakistan, Persevering Politician Promotes Peace

By Aja Rose Anderson

American University

Washington , DC

Democracy,

justice, compassion and human rights: on these ideals the

nation of Pakistan was founded. Yet today the country

teeters on the brink of total chaos as judges are sacked and

placed under house arrest, the constitution is suspended,

and unspeakable acts are committed on the people. This

is not the Pakistan envisioned by Muhammad Ali Jinnah.

Democracy,

justice, compassion and human rights: on these ideals the

nation of Pakistan was founded. Yet today the country

teeters on the brink of total chaos as judges are sacked and

placed under house arrest, the constitution is suspended,

and unspeakable acts are committed on the people. This

is not the Pakistan envisioned by Muhammad Ali Jinnah.

It is in the memory of the Quaid-i-Azam that leaders like Imran Khan work to restore Pakistan to her former glory; replacing corruption with rule of law, dictatorship with representative democracy, and torture and terrorism with a humane, compassionate state.

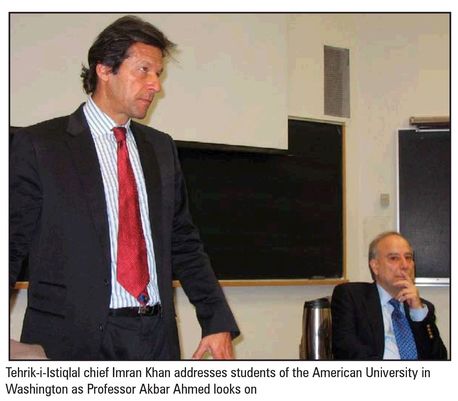

Khan came to the United States in the last weeks of January to speak to the American government about resolving the situation in Pakistan and to visit American University, where he lectured on Islam, democracy, and the future of his turbulent homeland.

Excitement was palpable Wednesday, January 23 as Khan entered the classroom of Ambassador Akbar Ahmed. Introducing Khan to the students and mobs of reporters, Ahmed highlighted his cricket background, with which the largely American audience was unfamiliar. “I know in baseball you can’t deliberately hit a batsman,” Khan later told the class, “but in cricket you can actually go for him!”

The professor also elaborated on his friend’s experience as a politician and philanthropist. It was Imran Khan’s politics that drew more students than the room could hold. The decision to transition from sportsman to public servant was the result of becoming a spiritual person. “There are no prizes for coming second in sports,” Khan pointed out. “If I succeeded in sports, I had that killer instinct. That sort of mentality makes you pretty callous. You get to thinking that the poor are poor because they don’t work hard enough...spirituality changed that mindset in me.” Khan told the class that he believed all religions asked the same thing of their followers: to become selfless, suppressing animal instincts, and therefore become part of a community.

Choosing to serve Pakistan seemed natural to Khan, because “the more you are given, the more responsibility you have to your country.” Smiling wryly, Khan told his audience that he did not have to be in politics; who in their right mind would choose a job that would lead to being jailed and chased by hit men?

Yet as a Muslim, he felt compelled to work toward establishing a truly just society, mirroring the dream of Jinnah. Khan believes fear is all that holds us back from achieving our true potential. In sports, there is the fear of injury and failure. These fears can translate to politics as well, which Khan joked about: “If you have a fear of death, you won’t go into politics in Pakistan!” The solution to fear for Khan was spirituality; faith in Islam taught him to forget his anxieties and take greater risks.

Yielding the floor to the questions of students, Khan fielded inquiries about his politics and the future of Pakistan. Asked about the government’s provision for his security, Imran revealed that all political figures in Pakistan have been warned they are in charge of their own safety. Khan then asserted, “To worry about dying — I don’t really. It’s a futile thing to think you can prevent death, especially in the sort of politics we are in.”

Describing a truly Islamic state, Khan told the students he believed Sweden was as close to that ideal as possible, as it upheld public morality by providing free healthcare and education for its entire population. He went on to explain to the classroom that the evolutionary process in the Muslim World is slow “because we don’t have democracy, we don’t have debate; because we don’t have debate the thought process has stagnated.”

The integrity, honor, and privacy of family life must be maintained, and the reaction to inundation by an alien culture is the rise of fundamentalism. Khan informed the class that Pakistan was more equipped for democracy than any other Muslim country, as it was visualized by a constitutionalist and lawyer. However, thanks to a series of wars between the nascent republic and India, security became the main concern and the army took over. “The people have always craved democracy,” Khan said.

“In some ways, it is the worst of times. A dictator does not want to leave power and he is systematically dismantling state institutions. The most important thing is justice.” Imran’s conclusion was not hopeless, however. He felt, given the backlash that has been seen in Pakistan against the repressive regime of Musharaf, that change is just around the corner. The judiciary stood up against the executive, and the lawyers’ community rallied behind the chief justice. This spectacle is visible to the international community

While he did not believe that the upcoming elections would be entirely free and fair, he acknowledged they were a step in the right direction. His mission here in America was to convince President Bush to stop aiding the clearly corrupt administration, and thereby send a strong message to the rest of the world. One point he stressed especially was that “the essence of democracy is engaging everyone.”

The attitude that some people’s perspectives are more important than other’s rubs Khan the wrong way. He maintained in particular that refusing to speak with identified terrorist and fundamentalist groups was anti-democratic. “To say that you can’t sit on the same table as these religious parties is very dangerous. You don’t want to push them to the wall, you want them to come into the fold.”

Khan believes reforming Pakistan requires “carrying everyone with you.” He highlighted the incredible clout of the religious lobby; once a politician is labeled anti-Islamic, their response is not rational.

Zalifikar Ali Bhutto outlawed a political party and alcohol. Musharaf, given millions to reform the madrassas, gave up the program when he was called pro-American and anti-Islamic. Thus engaging the parties who would be written off in America is crucial to enacting real and lasting change in Pakistan.

“You don’t want to be exclusive. Give them a common vision, and move all people toward this vision.”

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------