Muslims Serve Food and Friendship in Ramadan to Beat Far Right

By Yermi Brenner

Brunswick, Germany: In the early evening, before the daily fast was broken, SadiquAlmousllie, a 47-year-old with an inviting smile, held a large sign that read: "I am Muslim. What would you like to know?"

Islamic music played from inside the nearby tent and comfortable chairs were offered to tempt Brunswick residents to join the festivities.

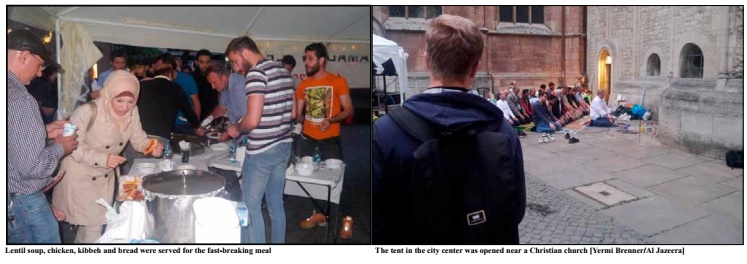

The city's Muslim community set up the Ramadanevent in the center of the city beside a large 12th-century Lutheran church, and only a few meters away from the spot where Almousllie and his family were verbally attacked last year.

"We are giving people the possibility to get to know Muslims, to get in a conversation," said Almousllie, who arrived in Germany almost 30 years ago as a university student.

Last year, a stranger shouted at him and his family: "Go home!"

He had replied: "This is our home. My children were born in this country, and this is their home."

But on this Ramadan evening, he approached passersby and encouraged them to ask him anything about Islam - with no topic off limits.

As the fast-breaking hour of 9:30pm (20:30 GMT) got closer, dozens of Brunswick's Muslims filled the tent.

This was the seventh consecutive year that the community set up a Ramadan tent to encourage inter-religious communication.

"I have actually never been to one of these events and I wanted to learn a little bit more about it," said Lisa-Marie Jalyschko, a member of the Brunswick City Council who works in the Volkswagen headquarters in nearby Wolfsburg.

"It is important to include different cultures and different cultural events in our city life. It is important to give publicity to these events to show that [Muslims] are also part of [our] society."

Izzat, a Syrian in his 20s who arrived in Germany 18 months ago and is studying German, was busy serving the food - lentil soup, chicken, kibbeh and bread.

"Germany is a Christian land. The majority of people don't know really about Islam and what Islam means," said Izzat, who requested anonymity because he has family members in Syria.

"Therefore, we should introduce ourselves to the community we live in."

Brunswick is 300km from Dresden, where the Patriotic Europeans Against the Islamisation of Europe (Pegida) is popular, and only 20km away from Salzgitter, a city that last October decided to ban refugees.

Almousllie, who serves as the head of the Central Council of Muslims in Lower Saxony, has noticed a significant increase in verbal and physical attacks against Muslims in the past two years.

Hate-mail insulting the Prophet Muhammad was delivered to the Brunswick mosque last year, and one afternoon, following communal prayers, a man opened the mosque door, yelled "dirty Muslims" and fled.

"It is a situation that is getting worse and worse," he said.

According to the German Federal Ministry of the Interior, more than 1,000 Islamophobic attacks were registered in 2017, the first year in which such data was recorded.

At least 33 Muslims were injured in attacks, which included assaults against Muslim women wearing headscarves and the vandalism of mosques and other Muslim institutions, the interior ministry said.

Germany's largest minority: Muslims are the largest minority in Germany.

They comprised 4.1 percent of the population in 2010, and 6.1 percent in 2016, mainly due to the arrival of refugees from Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan.

As the number of Muslims increased, the far right expanded with the growth of the Pegida movement and as the Alternative for Germany (AfD) party surged into third place in the last federal election.

But Islamophobia in Germany did not start recently, according to Professor Kai Hafez from the University of Erfurt, who has authored several books about Islam in the West.

Hafez explained that negative stereotypes about Muslims became more visible in the public discourse as Pegida and AfD politicized an agenda around Islamophobia.

Germany is now at the point where it must fight Islamophobia as it fought anti-Semitism in the middle of the previous century, according to Hafez.

"In the early 60s, a large part of the German population was highly anti-Semitic, and it was only when we started programs through education, through the mass media, through films that many people started to understand what anti-Semitism really means, and from that point on - let's say the mid-60s - that the situation really changed," he said.

"We should think about creating now large-scale societal initiatives along the same line," Hafez added.

"It requires a collaboration of the education system, academic, the mass media and the political parties to really change Islamophobia in society. Islamophobia is not something that will vanish without a concerted effort."Source: Al Jazeera News

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------