Secluded Muslim Community Draws out the Worst Online

By Rick Rojaz

Hancock, NY: Deep in the dense woods near the Catskill Mountains, a settlement was started decades ago by Muslim families, many of them African-Americans from New York City, who were seeking to distance themselves from neighborhoods they saw as dangerous and laden with corrosive influences.

Holy Islamberg was intended to be a refuge, a serene environment to pray and bring up children.

In the years since, the enclave’s residents have forged relationships with state and local law enforcement, and made connections with their white neighbors from nearby towns. They work alongside each other in medical clinics and offices. Their children are teammates in youth football and basketball games.

But residents of Islamberg have found that there is no such thing as a haven in the internet age.

Conspiracy theorists and anti-Muslim groups have sketched a false portrayal of the community as a hidden-away den of Islamic extremism. Last week, police in Greece, New York, roughly 200 miles away, arrested four young people who are accused of amassing a stockpile of firearms and homemade bombs with plans to target the community.

The plot was the second major one on Islamberg to be thwarted by authorities in recent years.

The threatened violence reflects how Islamberg has become fodder for a pernicious part of the internet, one steeped in virulent hate and misinformation spread by websites like 4chan and Infowars, alongside subjects like Pizzagate and QAnon.

“These kids in Greece, they’ve never been to Islamberg,” said Hussein Adams, chief executive of the Muslims of America and a resident whose family has lived in the community for three generations. “They go on the internet and they’re fed all this fake news and all this misinformation, and they come up with a plan.”

Adams and other residents said they subscribe to a faith based on love and respect.

And local authorities said the swirl of online conspiracy theories about Islamberg were unfounded.

“They are law-abiding,” said Maj. William F. McEvoy, the State Police commander in the region. “They are positive, solid members of the community.”

Islamberg has about 200 residents, some from families who have lived here for two or more generations, and covers some 60 acres outside Binghamton, near the Pennsylvania state line and about 150 miles from New York City. It is set back off a bumpy road on private property, up steep slopes, past pastures and alongside a creek.

The winter conditions can be punishing, with snow and ice making the community even harder to reach. Still, residents have a spread of land offering enough room to build homes and a mosque and raise livestock and crops.

Islamberg was started around 1980 by a group of mostly African-Americans who had converted to Islam in the 1960s and followed Sheihk Mubarik Ali Shah Gilani, a Pakistani cleric and founder of Muslims of America.

He encouraged his followers to flee large cities and build communes in rural areas where they could separate themselves from the crime and the violence they faced in their old neighborhoods and the decadence that, in his view, pervaded secular society. Over the years, his followers have set up about a dozen other villages similar to Islamberg, including ones in Virginia, Georgia and Tennessee.

The presence of a largely black community whose members wear Muslim garb has been conspicuous in the nearby small towns like Hancock that are populated with mostly white residents. Their arrival more than 30 years ago came with tension, but over time, the relationship warmed as residents of Islamberg became enmeshed in the broader community.

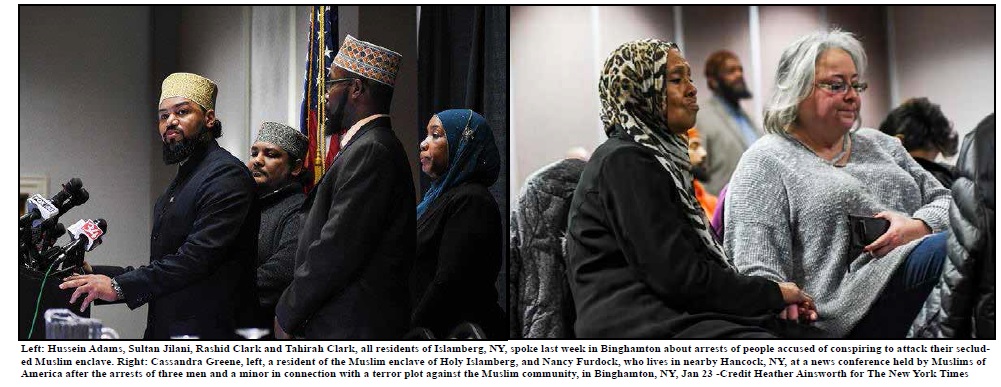

“We’ve never had a problem,” said Nancy Furdock, who has lived in Hancock — “two mountains over” from Islamberg, she said — for nearly two decades and has become friendly with people who live in the enclave.

She corrected herself slightly, “We have a problem with outsiders.”

“Why don’t they come talk to us?” she added, referring to those who circulate conspiracy theories about Islamberg online. “We’ll tell you what’s going on, which is nothing.”

In recent years, far-right Facebook groups have warned of an encampment governed by an oppressive form of Shariah law, which they claimed would encroach into broader society.

Documentary-style videos portrayed Islamberg as a Jihadi training camp and terrorist sleeper cell, and people who present themselves as national security experts have published reports online alleging a culture of “militant brainwashing,” forced marriages and doling out lashes and other forms of draconian abuse for violating its rules.

The community’s critics seized upon an arrest, in 2017, of a 64-year-old man accused of stealing ammunition in nearby Johnson City, which led authorities to find a storage locker stocked with powerful weapons.

Officials said at the time they had found “no indications there was a plan in place to commit an act of violence.” Still, the case served as fodder for purveyors of disinformation, who peddled false stories claiming the weapons were bound for Islamberg, that President Donald Trump had ordered a raid and that investigators had uncovered “America’s WORST Nightmare.”

Trespassers have been found attempting to sneak into the community or to fly drones over the property to conduct their own investigations. And a recurring ride of bikers has rumbled past Islamberg’s entrance in a caravan to alert the community to their vigilance.

“I don’t believe the people inside here are peaceful and are standing for the same thing we stand for,” Joseph Glasgow, an organizer of the demonstration, called a “ride for national security,” told the crowd that had assembled in a parking lot before setting off for Islamberg in 2017.

The speculation about terrorism has inspired more than protests. In 2017, a Tennessee man, Robert Doggart, was sentenced to nearly 20 years in prison over a plot to recruit a militia and storm the enclave. In a phone call recorded as part of a federal wiretap, Doggart said, “I don’t want to have to kill children, but there’s always collateral damage.”

The most recent threat of violence came last week after investigators in Greece, outside Rochester, thwarted an apparent plan concocted by a group who, officials said, had stockpiled 23 firearms and three homemade bombs.

Three men — Vincent Vetromile, 19, Brian Colaneri, 20, and Andrew Crysel, 18 — were arrested and charged with criminal possession of a weapon and conspiracy, and a fourth person, whose identity was not released because he or she is a minor, was charged as an adolescent with the same offenses.

It is unclear how the individuals were connected, but three of them had been Boy Scouts. In the days before the plot was uncovered, at least one of them, Vetromile shared far-right memes and conspiracy theories about border security and a government scheme to seize weapons. Authorities also said that the defendants had corresponded using Discord, a group chat app created for video gamers that became popular with far-right activists.

Vetromile and Colaneri remain in custody, according to jail records.

“Just imagine having to wake up and tell your children of such a plot, tell your children that their life was in danger,” said Rashid Clark, Islamberg’s mayor.

Much of the scrutiny directed at Islamberg centers on the community’s ties to Gilani, an elusive figure who became more widely known after the 2002 murder of Wall Street Journal reporter Daniel Pearl in Pakistan. Pearl, who was reporting on a story about the so-called shoe bomber, Richard C. Reid, was seeking an interview with the sheikh when he was abducted. (The sheikh is not believed to have been involved in the plot, counterterrorism analysts said.)

Suspicion has also sprung from the community’s purported association with an obscure Muslim group called Jamaat al-Fuqra, which is tied to the sheikh and has drawn the notice of law enforcement in the United States because of accusations of criminal activity beginning in the 1980s.

In 2002, after the gun-charge arrests of three people authorities said were part of Jamaat al-Fuqra, federal prosecutors described a “history of violence” involving the organization, including fire-bombings and murder. Islamberg’s leaders have denied a connection to the group.

And an analysis published in 2008 in the CTC Sentinel, a journal published by the Combating Terrorism Center at West Point, concluded that there was no evidence proving Islamberg was part of a covert training operation. Instead, the report said, “the presence of weapons (or even arsenals), nor weapons training are particularly unusual phenomena in rural America.”

The right-wing interest reflects “a certain amount of obsession that I don’t see how it’s possibly justified,” William Rosenau, one of the authors of the Sentinel analysis, said last week. “I think the fact that the members are Muslim and almost all African-American is a source of a lot of the anxiety. I think it’s straight up religious and racial fear.”

McEvoy, the State Police commander in the region, said the story of Islamberg reminded him of his own: His mother had moved their family from Brooklyn to Binghamton for a change.

“They believe in education,” McEvoy said. “They believe in hard work. They believe in raising their children with those goals in mind.”

A day after the most recent plot emerged, nudging Islamberg back under the glare of outside attention, community officials organized a news conference in a hotel ballroom in Binghamton. There, its leaders once again had to challenge falsehoods about them.

“Beautiful place to live, beautiful people to live with,” said Cassandra Greene, who was among the earliest arrivals to Islamberg more than 30 years ago.

After the news conference, Adams of Muslims of America marveled at his community’s resilience. He said he believed that the alarm and cynicism that has surrounded Islamberg had not seeped inside the community.

Indeed, he said, Islamberg has remained very much the same place his parents had sought, with tranquility among residents and the latitude to live out their faith. To him, that was most evident in the mornings. The community rises well before sunrise. People wash their bodies, put on clean clothes and perfume. They step outside, on the land where they hunt and raise much of their own food.

“We say our prayers to God almighty,” Adams said. “That starts our day, and that’s everything.”

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.