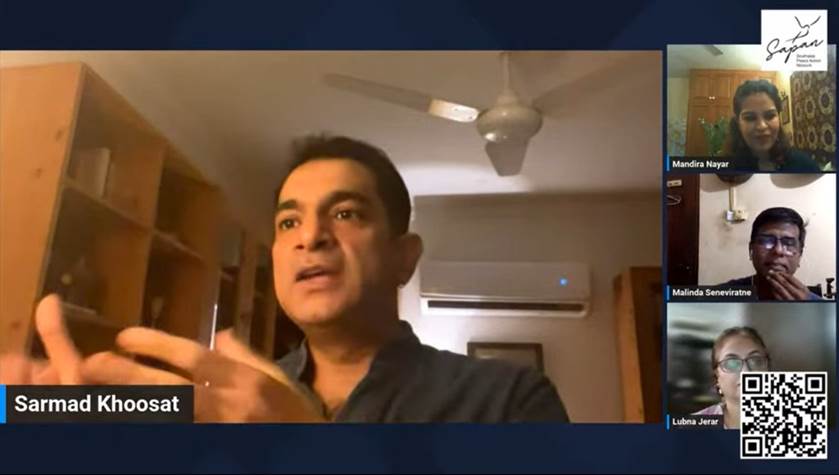

Sarmad Khoosat in discussion with Southasian journalists Mandira Nayar, Malinda Seneviratne and Lubna Jerar as part of Sapan’s first fundraiser

South Asian Filmmaker Sarmad Khoosat on Cinema That Defies Norms and Transcends Borders

By Arifa Khandwalla

“The moment the credits rolled, it was like a Shahrukh Khan film – people whistled and clapped,” said Indian journalist Mandira Nayar , addressing Pakistani film producer Sarmad Khoosat about a late-night show of his film screened recently in Delhi.

At the online conversation broadcast live last Sunday, Nayar recounted how she had been desperate to see Joyland since it burst onto the Southasian film scene after winning two awards at the Cannes International Film Festival. The Delhi show was “advertised for about half a day before it went live” added Nayar. It was a rainy day, with a long queue of people waiting for a pass. As she stood in line, several people approached her asking if she had an extra.

Watching Joyland that day “was one of the most touching and overwhelming experiences I have had for a very, very long time. It really brought me hope,” added Nayar.

Sarmad Khoosat along with Sapan members and volunteers

The joy on Khoosat’s face spoke to the artist’s need for appreciation, no matter how many hit films and TV plays he has to his credit.

For Khoosat, peace “is just the essence of a good life. It could be personal, it could be national, it could be between countries or it could be globally. The sense of peace is so quintessential to human existence.”

Joining the two in the discussion were journalists Malinda Seneviratne in Colombo and Lubna Jerar in Karachi. The discussion, part of the first fundraiser by Sapan, the Southasia Peace Action Network , underscored how film and art touch human experience and transcend borders.

Launched in March 2021, Sapan is a cross-border, inter-generational organization that Mandira Nayar said she has “personally seen grow to be a movement”.

And the response to the film Joyland in India “really demonstrates how films and creativity can actually soften borders.”

The discussion ranged from cross-border soft cultural exchanges to the challenges of filmmaking in Pakistan and Sarmad’s philosophy of art. Poet and theatre patron Arvinder Chamak in Amritsar hosted the evening and began with a Persian-style invocation: “ Ibtida hai Rab e Jalil key Ba-barkat naam sey… Jo dilo’ key bhed behtar jaanta hai” (invoking and initiating with the name of Divine Almighty who knows all of us better than we know ourselves).

The discussion highlighted how Pakistani movie and theatre goers lament the banning of Indian films in Pakistan and Indian audiences clamor for Pakistani dramas. Commonalities of language, music and culture developed over thousands of years cannot be erased, as elements in both countries are trying to do, rewriting history and marginalizing ‘the other’. Efforts to rewrite textbooks have reached as far as California . But it is not easy to decouple shared histories and cultures.

Addressing this issue, Khoosat commented on the unnaturalness of the approach attempting “to somehow make us believe that our root of that whole tradition is not common. It is common. You cannot take the seeds and the color, the folklore, the music, the sounds, the people from the region.”

The arts are “an easy target for political point scoring” but attempts have been unable to stop cross-border film exchanges. In Pakistan, the film industry, which died during the 1970s, is only now finding its way back, he added.

Indian audiences of Khoosat’s drama series Humsafar would love for such dramas to be created by India, said Nayar. She expressed her wonder at how a conservative Southasian country like Pakistan is producing edgy radical films like Joyland and Churails.

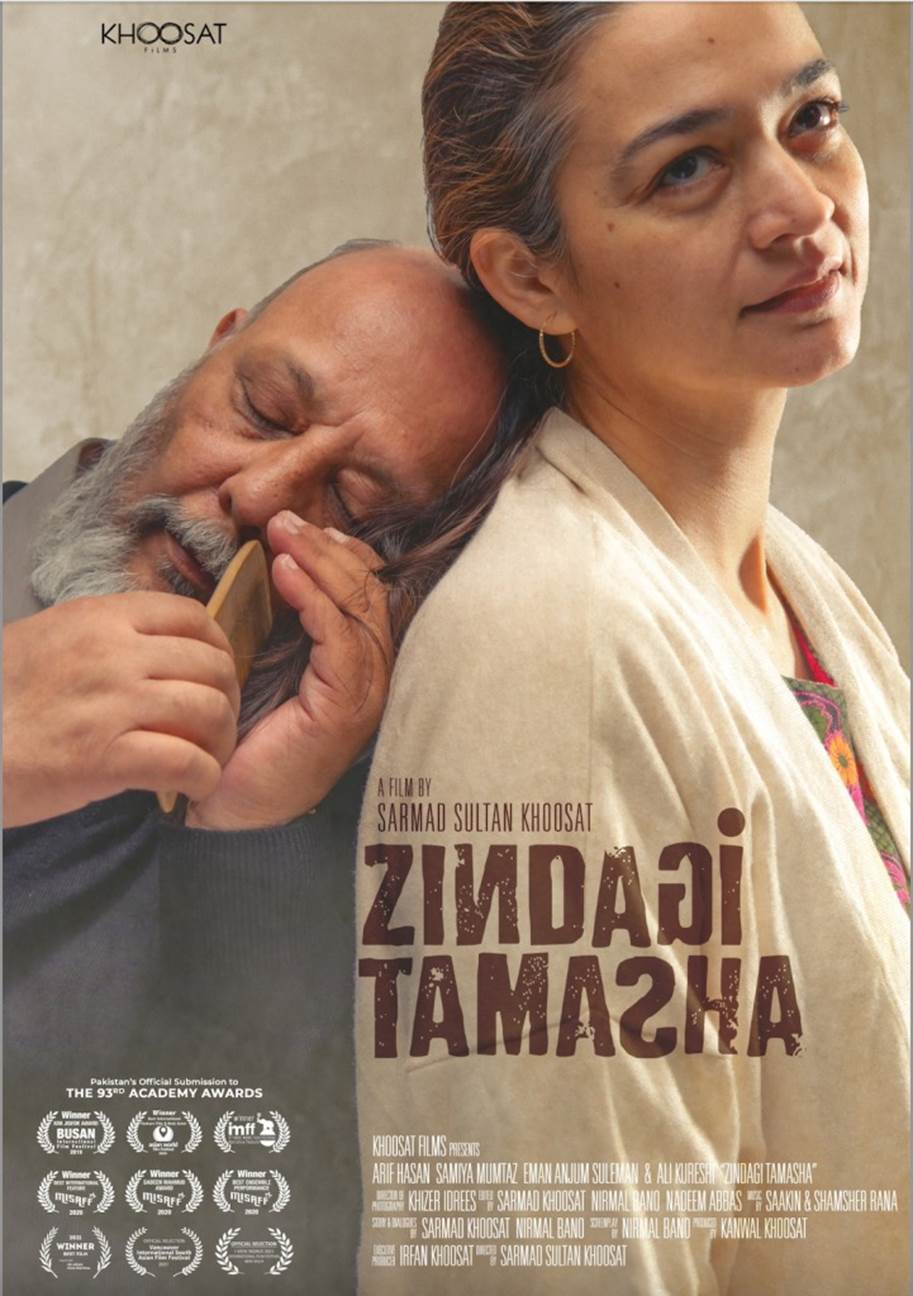

It’s a struggle, replied Khoosat. Despite trying his utmost to follow political sensibilities, his film Zindagi Tamasha is still banned in Pakistan. He feels stuck. Joyland too is banned in his home province Punjab, which has the largest population.

“When films like these do not get their rightful share of audiences here at home, I feel it’s a big failure, not our failure maybe but a collective failure of whoever is part of the big board,” he said.

A poster for Zindagi Tamasha : Banned but still standing

Despite online streaming channels, Pakistanis still find it difficult to access these movies. In the meantime, Zindagi Tamasha was Pakistan’s entry to the Oscars in 2021 and both films have won many awards in festivals globally. While Sarmad didn’t say it outright, banning films affects the financing of future such films.

So, will this renaissance in the Pakistan film industry be stunted due to the banning of films? Why hasn’t India released radical arthouse films? Could it be as Khoosat said, that while India banned movies annually it was until now rare in Pakistan?

And what is the impact of “radical” films like Joyland? Responding to a question from Lubna Jerar, Sarmad explained that he had a difficult time after Joyland dealing with the threats that he received online. He never knew how serious these threats were or if they would materialize from social media. Their transgender actors also received threats.

While Joyland is set around the relationship between a transgender woman and a married man, it is also about feminism and societal expectations on women in Pakistan. Lubna said that Joyland was released at a delicate time for the transgender community and that they felt the film put them uncomfortably in the spotlight.

Similarly, Khoosat spoke about the personal cost when Zindagi Tamasha was targeted by right-wing parties taking out processions to ban the film and social-media posts calling to hang him. Most of the conversation in Pakistan revolved around the banning of the film and “not the work itself.”

He has made the film available for a limited time for the Sapan fundraiser.

In response to a question from Malinda Seneviratne, Khoosat said that art doesn’t have to be about leaving a message. “It could just pose a question. It could just create that nice marinade where you put something, and people will just come out soaked in that and thinking about that.”

He espouses fluidity in his characters and films. Joyland for example has multiple storylines with several central characters. “Art doesn’t have to be circumscribed in such linear lines,” he said.

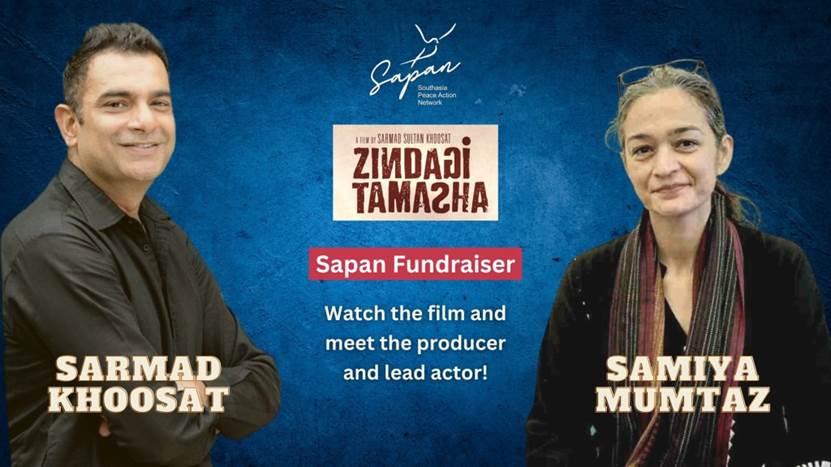

Sapan will have a follow-up screening and discussion with Sarmad Khoosat as well as the acclaimed actress Samiya Mumtaz, who plays the lead female role in Zindagi Tamasha, this coming weekend. Supporters contributing to the fundraiser will have the opportunity to see the film for a limited time, plus engage online with Khoosat and Mumtaz on Sunday, 23 July.

(Arifa Khandwalla is an environmental activist based in Princeton, NJ, USA, where she is on the city’s civil rights commission. In her previous life among other things she conducted research in climate science and was an editor at Chowrangi, a Pakistani diasporic magazine.

This is a Sapan News syndicated feature.)